Update: Facing a campaign for his recall, Alaska Gov. Michael J. Dunleavy announced on Tuesday that he had reached a compromise with the University of Alaska (UA) to ease drastic budget cuts. Rather than slashing $135 million from the university’s budget immediately, UA has agreed to reduce spending by $70 million over the next three years.

Alaska Republican Gov. Michael J. Dunleavy’s massive budget cuts to the University of Alaska (UA) system have serious repercussions for all members of the school community, but they pose unique challenges for Native students.

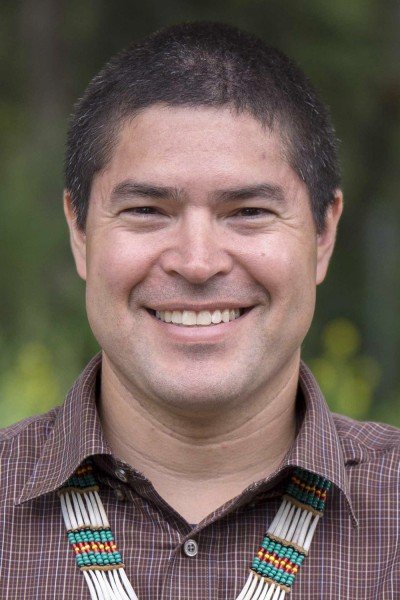

Historically, UA has served as the preeminent institution of higher education for this population. At its flagship campus, University of Alaska, Fairbanks (UAF), approximately 20 percent of the student body is Native Alaskan, a percentage roughly the equivalent to the overall Indigenous population in the state, according to Evon Peter, UAF’s vice chancellor for rural, community, and native education.

These students tend to be first-generation and come from low-income rural areas. Many are older than the typical high school graduate and bear significant family and cultural responsibilities in their home villages, Peter says.

UA has long been a leader in the preservation of Alaska’s Indigenous culture, offering a rich portfolio of unique programs and services geared toward this underrepresented group. With $136 million to be cut from the UA system budget, these offerings are bound to be affected, Peter says.

Here’s a look at some of UAF’s services that will be affected by the funding cuts, according to Peter, who is quick to point out that these programs rely on of a variety of personnel within the broader university system:

- UAF’s Alaska Native Language Center teaches and conducts research about the state’s 20 Indigenous languages. The center plays a key role in their tenuous preservation. In 2018, the Alaska legislature declared each of them official state languages, Alaska Public Media reported.

- UAF’s Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) is one of three national centers leading Native American and Alaska Native youth suicide prevention efforts, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).Native Alaskans who are working toward an entry level certificate in counseling have the opportunity to participate in this high-level research, Peter says.

- UAF’s Rural Student Services (RSS) office offers comprehensive advising to Indigenous students, many of whom experience a major culture shock as they enter college from extremely remote villages, according to Peter.

- UAF offers unique degree programs focused on the preservation and welfare of Native peoples, from bachelor’s degrees in Alaska Native Studies to PhDs in Indigenous Studies.

- The Rural Alaska Honors Institute (RAHI) is a summer bridge program for Native high school juniors and seniors. They can earn up to 10 college credits through the program.

- The Eileen Panigeo MacLean House, a dormitory specifically for Alaska Native students at UAF, offers the chance for members of this underrepresented group to uphold their cultural identity and give and receive peer support.

These programs do not include other unique offerings for Native Alaskans at the University of Alaska Anchorage and University of Alaska Southeast.

If these programs or others like them are cut, UAF English Professor Sara Johnson fears Alaska Native students may lose the opportunity to both participate in their culture and earn a college degree.

“Some students will have to choose between remaining on tribal lands and leaving the state entirely for a decent education. And that’s not just students. It’s [Indigenous] faculty as well,” she says. “To force people to make that choice, it is violent.”

Those who stay enrolled at UA will also likely face significant challenges as the university system shifts toward an online learning model to cut costs. This mode of learning is not conducive to some of the subtle, nonverbal cues that form an important part of Native Alaskan communication, according to Peter, who is Neetsaii Gwich’in and Koyukon and a former tribal chief.

“In some of our cultures, people raise their eyebrows to say yes,” he says. “A professor may ask a student a question and a student raises their eyebrows, but the professor has no idea that they’re communicating with them.”

Another major concern is the fact that many rural villages don’t have the bandwidth to support video streaming, which is typically an essential component of online learning. Purchasing this level of internet connectivity in remote areas can be steep. A member of Peter’s home village, for example, told him that he’d have to pay $250 to $300 a month to be able to watch presentations online.

Peter says retaining Indigenous students and relevant programs will depend on having a systemwide Alaska Native administrator who can advocate for their needs as the university restructures itself.

“We pride ourselves as an institution that we are on a pathway to having degree programs, courses, and approaches that uphold the highest respect for the diversity of all our students, including our Alaska Native students,” he says. UAF demonstrates this priority by instituting a new Alaska Native Studies course requirement for all students, he adds.

“We’re in an unprecedented time of uncertainty and complexity as a system and as a state, but I continue to stay focused on the fact that we have a very clear and powerful vision of serving Alaska Natives and people from marginalized communities — and serving them well,” he says.

Ginger O’Donnell is a senior staff writer for INSIGHT Into Diversity.