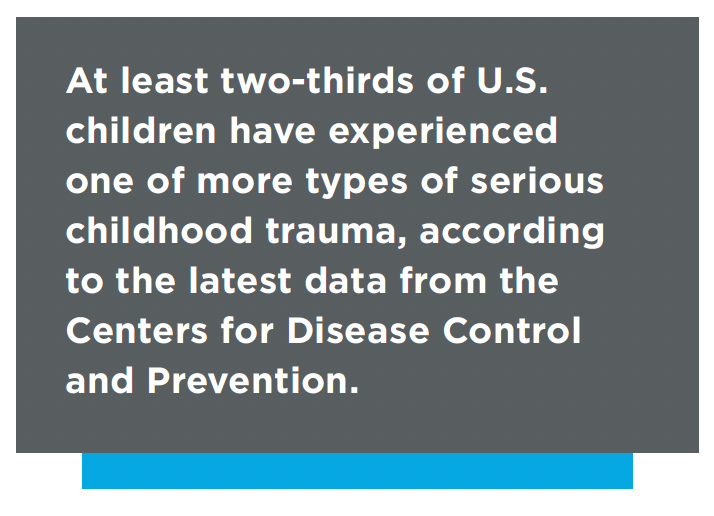

In recent years, a growing number of schools of education have begun focusing on trauma-informed teaching practices to help educators holistically address negative academic and social outcomes for students. Now, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread racial injustice, and a host of other major stressors for U.S. youth, these concepts have become more popular, and important, than ever.

“When the pandemic came, people really became concerned and interested in new traumas that were [affecting] students,” explains Regina Rahimi, EdD, a professor of education at Georgia Southern University. “Not only were students isolated, but if they were in an abusive household or they lived in a community where violence was prevalent, these things all became more pervasive in their lives, so that trauma was just further exacerbated.”

By applying trauma-sensitive principles to the classroom, teachers can help young people overcome the negative educational outcomes of growing up in these kinds of situations. This approach emphasizes understanding the ways that such environments can affect student behavior and promotes classroom practices that can mitigate trauma’s impact on socioemotional development.

While trauma-informed care has long been a core of other professions, experts say it is only now beginning to truly gain traction in education. Prior to the pandemic, Rahimi and her GSU colleagues surveyed 800 educators across Georgia and found that teachers “are generally aware of trauma amongst their students, but their typical response is to refer them to the counselor,” according to a January 2020 press release. Rahimi and her team developed a yearly online conference, the Trauma-Informed Education Symposium (TIES), to empower teachers to better serve struggling students.

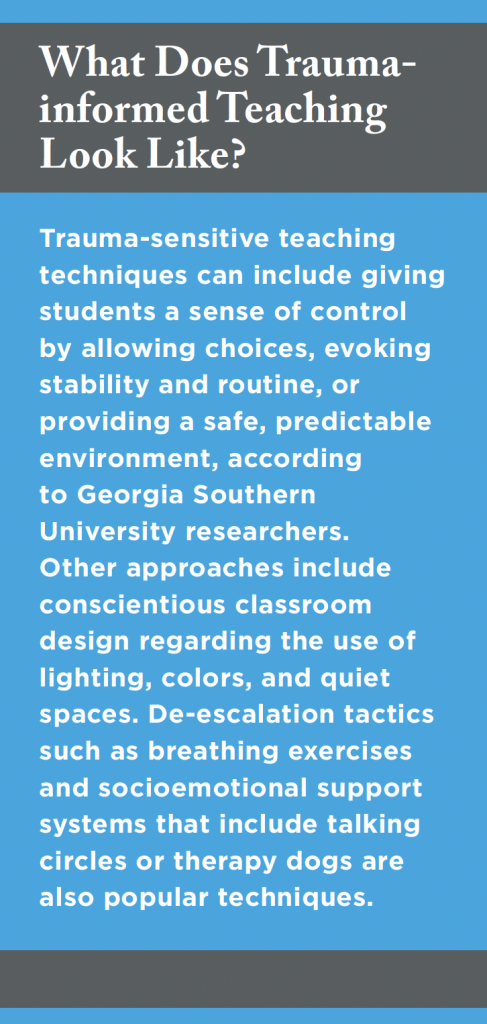

Rahimi says the goal of TIES, which is currently in its third year, is not to “turn teachers into counselors or mental health clinicians” but to provide the skills necessary to prevent re-traumatization. Participants learn about techniques for creating safe, predictable classroom environments, incorporating socioemotional skills and positive coping mechanisms into lesson plans, de-escalating unruly student behavior, and more.

Rahimi says the goal of TIES, which is currently in its third year, is not to “turn teachers into counselors or mental health clinicians” but to provide the skills necessary to prevent re-traumatization. Participants learn about techniques for creating safe, predictable classroom environments, incorporating socioemotional skills and positive coping mechanisms into lesson plans, de-escalating unruly student behavior, and more.

Rusty Earl, a former K-12 educator who currently serves as a video producer for the Kansas State University (K-State) College of Education, says that students who are pursuing a career in teaching should understand that they do not need to be experts to make a difference with powerful, trauma-informed techniques. He recently directed a K-State documentary, Becoming Trauma Responsive, that highlights how educators in the Midwest have adapted to student needs during the pandemic by using basic trauma-sensitive approaches.

“Being calm and in the right presence of mind does so much more to help students than knowing some magical words or having all of the brain science down,” Earl says. Multiple experts who were interviewed for the film emphasized that simply providing a classroom environment where students know they are safe and have a teacher whom they can trust can make a significant difference.

In addition to the film, K-State plans to roll out new trauma-informed coursework for education majors in fall 2022, according to Earl.

Other schools are increasing their trainings as well. Some universities have multidisciplinary trauma-informed learning centers or offer graduate certificates specializing in this area. Ithaca College in New York recently hosted a trauma-informed workshop to help current and future teachers learn practical methods to “promote health and wellness, engage learners, and provide safe spaces for learners to succeed, and increase [their] own wellness,” according to the school’s website. At North Carolina State University, researchers are conducting an interdisciplinary project titled Trauma Informed Practice Support in Schools and Communities that brings educators and social workers together to discuss best practices.

Other schools are increasing their trainings as well. Some universities have multidisciplinary trauma-informed learning centers or offer graduate certificates specializing in this area. Ithaca College in New York recently hosted a trauma-informed workshop to help current and future teachers learn practical methods to “promote health and wellness, engage learners, and provide safe spaces for learners to succeed, and increase [their] own wellness,” according to the school’s website. At North Carolina State University, researchers are conducting an interdisciplinary project titled Trauma Informed Practice Support in Schools and Communities that brings educators and social workers together to discuss best practices.

“A lot of times, when difficult topics come up, it’s natural to want to just quickly divert from that conversation, but that can be really difficult for children,” Angela Wiseman, an associate professor of literacy education who is leading the project, explained in a press release. “If they’re sharing their feelings and coming to you for that, and you’re not sure how to acknowledge it, it can cause them to re-experience those feelings.”

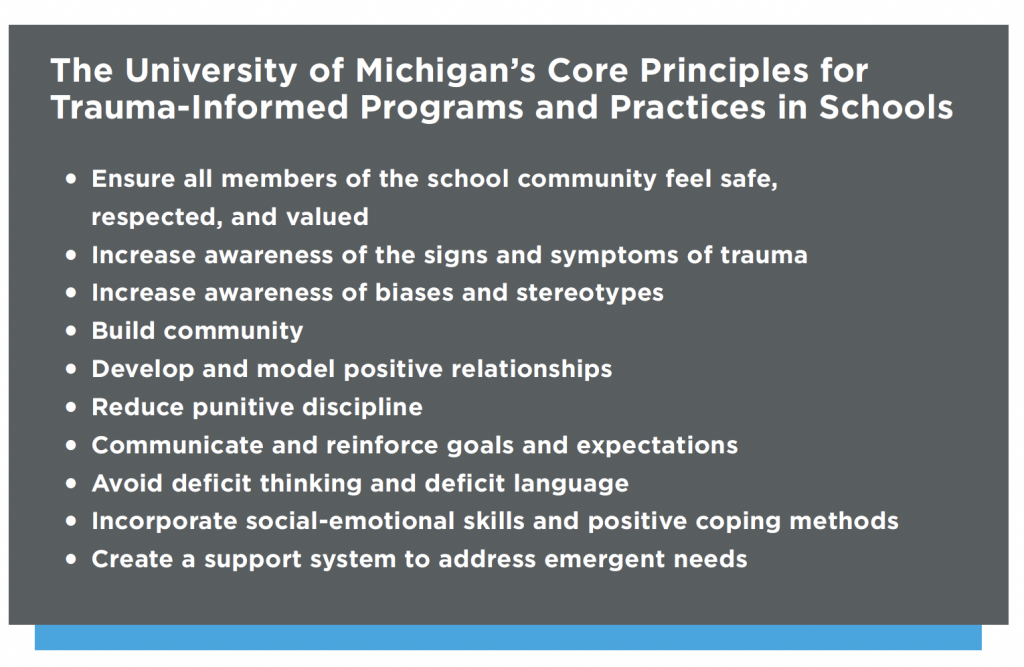

Such lessons may be especially valuable for teachers of underrepresented students. Young people of color and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are especially vulnerable to trauma due to racial stress and economic hardship that can lead to mental health issues such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorders, and sleep disturbances, according to the Family-Informed Trauma Treatment Center and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. The University of Michigan’s 2021 Trauma-Informed Programs and Practices for Schools notes that “racism, prejudice, and the mistreatment of people of color and other marginalized identities” compound the effects of other traumas. Furthermore, “[i]mplicit biases and stereotypes about children of color and others with marginalized identities can lead to actions that are harmful, and they strain relationships that children with trauma histories need to heal.”

Such lessons may be especially valuable for teachers of underrepresented students. Young people of color and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are especially vulnerable to trauma due to racial stress and economic hardship that can lead to mental health issues such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorders, and sleep disturbances, according to the Family-Informed Trauma Treatment Center and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. The University of Michigan’s 2021 Trauma-Informed Programs and Practices for Schools notes that “racism, prejudice, and the mistreatment of people of color and other marginalized identities” compound the effects of other traumas. Furthermore, “[i]mplicit biases and stereotypes about children of color and others with marginalized identities can lead to actions that are harmful, and they strain relationships that children with trauma histories need to heal.”

As far as implementing trauma-sensitive approaches, Rahimi says, different schools, departments, and organizations first need to have a commitment and adopt universal practices such as making classrooms as stress-free as possible.

“The pandemic certainly brought forward that we do have mental health and socioemotional needs in our communities and in our schools and in any work environment,” she says. “The big thing is not to retraumatize people by putting them in stressful, demeaning environments.”●

Mariah Stewart is a senior staff writer for INSIGHT Into Diversity.

This article was published in our April 2022 issue.