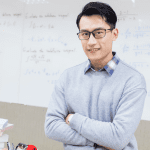

James Chan

When James Chan was 11 years old, his father was killed by a drunk driver. Chan went from living a relatively privileged life in New York City to gaining firsthand experience with the challenges that lower-socioeconomic households face.

Living off of his immigrant Chinese mother’s minimum wage job and his father’s survivor benefits, Chan relied on programs like Medicaid and free and reduced school lunch to get by.

Despite these hardships, he went on to earn his bachelor of arts in business administration and political science from the University of Florida in 2012. The obstacles he faced also influenced his decision to pursue a master’s in public policy (MPP) from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. He earned his MPP in 2014.

[Above: James Chan speaks with prospective students at the Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs in Minneapolis.]

Chan, who identifies as Chinese American and LGBTQ, says those with intersectional identities need to work together to coordinate public policy to benefit multiple underrepresented groups simultaneously, not just one at a time. “It can’t just be one or the other, but how do we all work together to advance the common good?” he says.

Chan’s perspective on intersectionality came partially from his experience at a nonprofit organization called the Florida 501c3 Civic Engagement Table. The organization is focused on increasing civic engagement among underrepresented communities, from Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to LGBTQ individuals.

Chan worked with approximately 50 nonprofit partners, all of which specialized in separate advocacy areas, sometimes concentrating specifically on one underrepresented group. “There are so many common issues and values shared between these groups, but there’s a lack of coordination between them. So, my work was to really work with all these partners to try to increase specific engagement capacity of [different] groups,” Chan says.

One of his first forays into public policy was as an intern for the Florida NEXT Foundation, founded by former Chief Financial Officer of Florida Alex Sink. As research director for Florida NEXT, Chan examined what other states had done to motivate startup businesses to come to their states and developed strategies for making Florida a friendly place for young business owners.

Today, Chan serves as Florida state director for the State Innovation Exchange, a national organization where he builds partnerships with legislators who are advancing and defending progressive policies.

Chan also focuses on volunteering his time to charity work. He served on the founding board of a nonprofit organization called Enterprising Latinas, which helps women support themselves by starting small businesses. In yet another role, he is the Tampa Bay chapter director of the New Leaders Council, a nonpartisan organization that hosts a free, annual fellowship program in all 50 states with the goal of training the next generation of progressive leaders.

In the same vein, he serves on the Alumni Advisory council of the Public Policy and International Affairs Program. “Being involved in these two groups has really given me hope about what’s possible for our future,” he says. “What I see every year in our alumni, our new fellows, is people who are brilliant in their work and are hungry to change the world,” he adds.

Angie Jean-Marie

Angie Jean-Marie, a first-generation American woman and first-generation college student who earned her MPP at the University of Southern California (USC) in 2015, describes the trajectory of her career as a process of “leaning into doors that open.”

She decided to pursue a degree in the field after working for three years as a legislative assistant for former U.S. Rep. Donna F. Edwards, an experience that impressed upon her the role of special interest groups in the legislative process. She attended USC’s Price School to “fortify [her] knowledge of policy and analysis.” During her studies, Jean-Marie learned about different avenues policymakers can pursue, such as pushing for social responsibility in corporations and working for local government.

She stayed in Los Angeles after graduating, landing a job at the Goldhirsh Foundation, which invests in solving social issues in the city. Jean-Marie says her proudest accomplishment at the foundation was supervising a program called “LA2050.” She managed three rounds of a challenge that awarded $1 million grants to winners whose projects enhanced the lives of city residents through education, entrepreneurship, sustainable public spaces, and more.

The money helped fund organizations such as the Lost Angels Children’s project, which teaches car restoration as both an after-school program and an opportunity for job skills training. She also helped finance others such as the L.A. Bioscience Hub, a group that works with companies to place community college students in biotech jobs around the city.

After her work at Goldhirsh, she became director of a national campaign called #VoteTogether, an initiative of the nonprofit Civic Nation in Washington, D.C. The initiative aims to increase voter turnout and is based on the findings of leading civic engagement researcher and Columbia University professor, Donald Green. Green “found that by making voting about celebration and community, we can increase turnout by 4 percentage points,” Jean-Marie says.

Being a part of the initiative during the 2018 midterm elections, when a record number of individuals from historically underrepresented groups were elected to public office, was “really inspiring,” she adds.

Originally an “east-coaster” who grew up in Westbury in Long Island, N.Y., which she describes as a “majority-minority community,” Jean-Marie appreciates the opportunity to make an impact on the lives of those working and living in the city of Los Angeles.

“L.A. has all the problems that I think the rest of the country is grappling with. Given the scale of the city — the city itself has 4 million people, the county has 10 million, and the metro area has 20 million — it’s a pretty significant scale to think about how to address the issues,” she says.

Another reason she is passionate about social change in Los Angeles, she says, is that the city’s demographics reflect the country’s future. “I hope L.A. can serve as a great test bed for new innovations and problem-solving that can be modeled in other places across the country.”

Juliana Pino

After studying East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago and working for several years at the U.S.-China Chamber of Commerce, Juliana Pino decided to pursue a path in public policy and environmental justice. She attended the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she earned both a Master of Science in Environmental Policy and Planning and Environmental Justice as well as an MPP from the Gerald R. Ford School.

For Pino, her two areas of concentration — East Asian civilizations and environmental justice in public policy — are not unrelated. “In both areas of study, I am trying to understand the relationship between the lives of everyday people and the decisions their government is making about them,” she says.

She serves as policy director at the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), a community-based organization located in a high-density, low-income, predominantly Mexican neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. Local parents founded LVEJO after some of their children became sick because of a roof refurbishment project that went on while students were at elementary school. The parents were able to shed light on hazards including asbestos and lead paint in the facility. As Pino describes it, “After that big project happened, the parents were still together and said, ‘What else can we work on [in the neighborhood]?’”

Pino leads a variety of initiatives as part of her work with LVEJO, such as combatting the pollution from “massive industrial facilities” near the community that causes health problems. She advocates for alternative energy solutions that not only create a healthier community but also offer residents employment opportunities.

Pino is also engaged in local anti-racism work, supporting organized efforts to counteract police brutality. She sees police violence and industrial pollution as part of the same “continuum of violence against black and brown communities.”

“[There are] these industries perpetuating what we call slow violence, killing people slowly through their toxic poisons, and then you have the fast violence of literal physical attacks coming from the police and incarcerated systems,” she says.

As an Afro-Indigenous Latina who also identifies as queer, Pino views her identities as a strong asset for promoting self-determination among local community members who likewise come from underrepresented groups. In addition, she emphasizes the need for more women of color in the field of public policy, acknowledging that she also faces significant “structural barriers” as a result of her race and gender.

Despite these challenges, she encourages other young women of color to enter the field of social justice and public policy. “In order to make changes to broken systems while we figure out how to dismantle them,” she says, “we have to address them at structural levels, which means getting involved in decisions. It’s a way to directly exert some control over our own futures and our own lives.”

Ginger O’Donnell is a senior staff writer for INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in our March 2019 issue.