A graduate student assistant in the United States earns on average $18,600 annually, according to the employment website PayScale. Those at the top earn nearly $30,000 per year at most, while the bottom 10 percent earn approximately $12,000.

Many graduate employees say their stipends are simply not enough to live on and amount to exploitation considering the significant amount of labor required of them. At research institutions across the country, a growing number of these workers are hosting sit-ins, rallies, and strikes to demand better compensation and support.

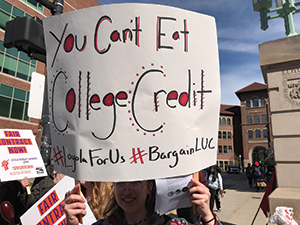

[Above: Loyola University Chicago graduate assistants and their supporters participated in a mass walkout on April 24, 2019. Photo credit: LUC Graduate Workers’ Union, SEIU Local 73].

Illinois has become a center for this movement. Graduate student assistants at multiple research institutions there, including University of Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and Northwestern University, have within the last year held protests for better pay and benefits. Those at Loyola University Chicago (LUC) are embroiled in a lengthy and contentious battle to be recognized by the administration as employees with collective bargaining rights.

“The position of the Loyola administration has for the last two years been that we are not actually workers, just students, and they know they can get away with that because of the current makeup of the NLRB board,” says Abram Capone, a third-year philosophy PhD student.

NLRB, or the National Labor Relations Board, is a federal agency whose members are appointed by the president to oversee employee unionization. Under President Barack Obama, the NLRB ruled that graduate assistants at private universities are employees and can therefore negotiate for better pay and other employment benefits.

Yet LUC and some other private research universities across the U.S. maintain that teaching and research assistants are classified as students, not employees. Movement supporters say LUC and other private institutions that take this stance know that any legal challenge against them would have to go before an NLRB with members appointed by President Donald Trump.

Yet LUC and some other private research universities across the U.S. maintain that teaching and research assistants are classified as students, not employees. Movement supporters say LUC and other private institutions that take this stance know that any legal challenge against them would have to go before an NLRB with members appointed by President Donald Trump.

According to the LUC website, “graduate students who are engaged in teaching and research as part of their academic program are fundamentally students. … [T]hey are not eligible for union representation.” The university did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

If the university recognized LUC’s graduate assistants as employees, their union, which is represented by the Service Employees International Union Local 73, would be able to bargain for increased transparency in the assistantship assignment process, better healthcare benefits, and higher wages, Capone says. “Right now, all we’re asking for is a seat at the table. [The administration] has made it a clear that they value communication, … but we can’t have open dialogue if we can’t even agree on the terms of what we’re asking, which is to stop acting illegally in violation of the NLRB ruling and negotiate with us in good faith as a union,” he says.

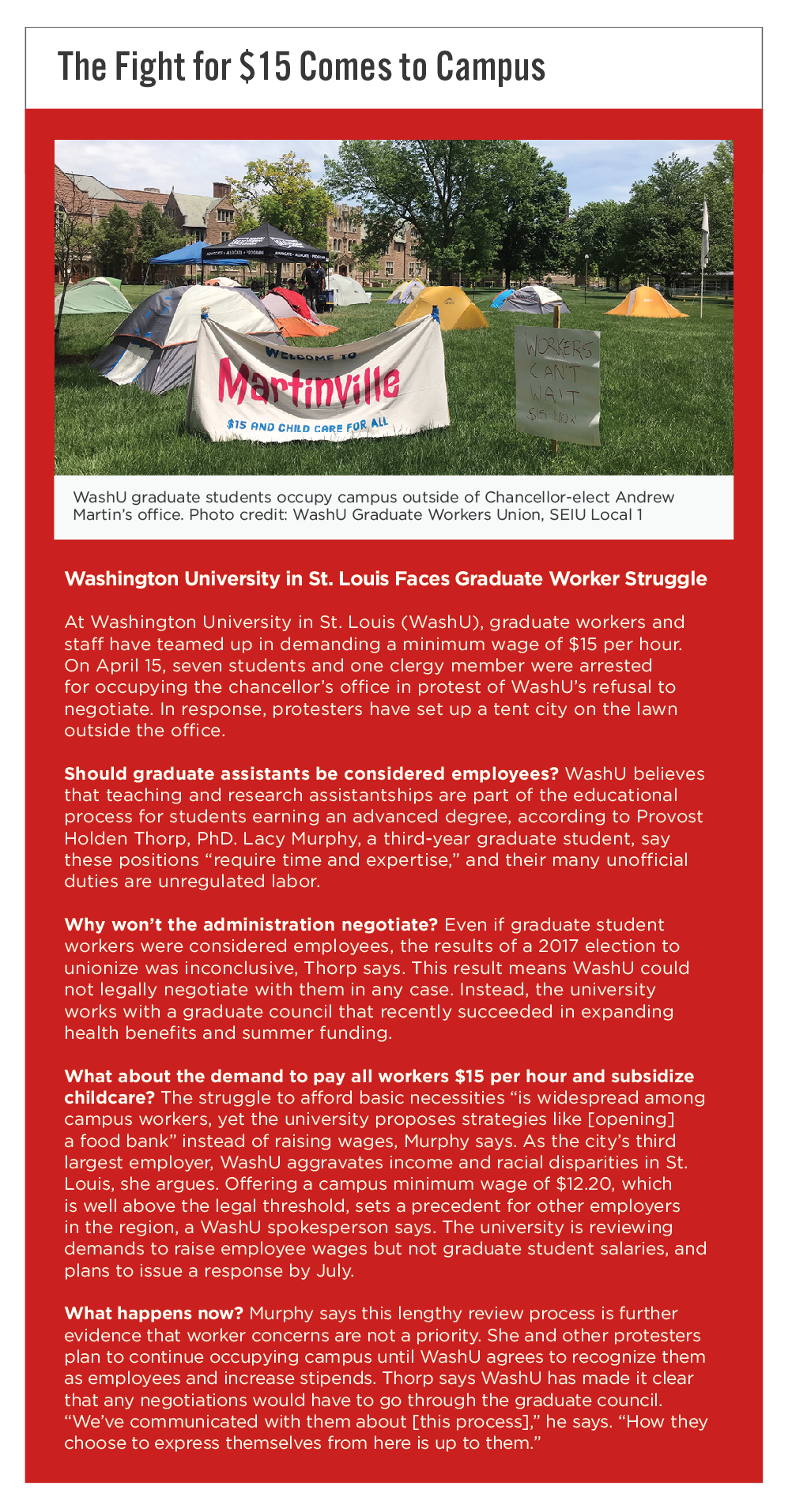

Over the last several weeks, graduate workers have intensified pressure on LUC through a variety of protests. On April 16, they and their allies held a sit-in in front of the president’s office. Seven students were arrested. On April 24, they held a mass walkout that included both graduate students and undergraduate student supporters. Members of the clergy, faculty members, and local politicians have joined in solidarity with the workers at multiple rallies.

“[The dean of the graduate school] pointed out recently that if we wanted to benefit ourselves and work towards our futures, then maybe we should stop the activism and start working on our studies,” Capone says. “If the administration actually cared about us finishing our degrees quickly, then I think [they would provide us with] adequate healthcare and a living wage so that we don’t have to work second or third or fourth jobs.”

“[The dean of the graduate school] pointed out recently that if we wanted to benefit ourselves and work towards our futures, then maybe we should stop the activism and start working on our studies,” Capone says. “If the administration actually cared about us finishing our degrees quickly, then I think [they would provide us with] adequate healthcare and a living wage so that we don’t have to work second or third or fourth jobs.”

At many institutions, graduate assistant contracts forbid or strongly discourage outside employment. During summer months, however, many of these workers take on multiple, temporary jobs to get by, Capone says.

Base pay for teaching and research assistants at LUC is $18,000. According to a living wage index developed by MIT, the living wage for a single adult in Chicago is $27,700.

John Hawkins, a fourth-year PhD student in English, says traditional graduate assistantships are designed to support the stereotypical college student: single, healthy, and young. As a married father of a 1-year-old, he and his family struggle to get by under policies that disadvantage nontraditional students. Getting coverage for his wife and child under LUC’s graduate assistant health plan, for instance, costs $6,000 annually. The money is due in a lump sum in the middle of summer, during which time he and most other graduate assistants do not receive a stipend.

Hawkins and Capone both rely on others for assistance. Capone is covered under his parents’ health insurance. Hawkins has family members who lend him money to get through summers. Many students, especially those who come from low-income backgrounds, aren’t so fortunate both men say.

Both say they’ve known graduate students who left their programs because they could not afford to continue or were too burned out from the workload. The average attrition rate for graduate students is nearly 50 percent, according to research.

At public institutions, graduate assistants automatically classify as employees under state collective bargaining rights. At UIC, teaching and research assistants formed a union in 2004 and have successfully negotiated several reforms since that time, says history PhD student Jeff Schuhrke.

At public institutions, graduate assistants automatically classify as employees under state collective bargaining rights. At UIC, teaching and research assistants formed a union in 2004 and have successfully negotiated several reforms since that time, says history PhD student Jeff Schuhrke.

Over the last year, however, graduate workers felt that their desire for a more equitable contract, including a living wage, was falling on deaf ears.

“We had [union] members come to the bargaining table [with the administration] and tell their stories of how they were struggling. Some of them were in tears talking about their financial struggles and how it affects mental health,” Schuhrke says. “But it was only when we went on strike that the university realized they had no choice but to listen to us.”

After 13 months of “escalating protests,” the students went on strike on March 18, essentially “shutting down” the university, Schuhrke says. Without graduate teaching assistants, hundreds of classes were canceled over the course of the three-week strike.

In the end, UIC agreed to meet the students’ demands, including implementing new guidelines to make the process of securing an assistantship more transparent. Another major victory was being able to waive a $2,000 annual fee that “was essentially 10 percent of our pay,” Schuhrke says, and getting fees for international graduate students cut in half.

At some research universities, campus leaders have been proactive in improving the graduate student experience. Georgetown University received widespread praise when it, as a private institution, supported its graduate assistants’ decision to unionize. Emory University in Atlanta gained national recognition last fall when it announced it would raise the graduate assistant stipend by nearly 30 percent over the next three years. And Southern Illinois University Edwardsville recently announced the administration had revised its budget in order to increase teaching and research stipends and will soon begin meeting with its graduate worker union to discuss salary expectations.

Graduate students owe it to themselves to become informed of their rights and “stand up for each other,” says Jonathan Bomar, director of employment concerns at the National Association of Graduate-Professional Students (NAGPS).

“We cannot always be the ones squeezed for cash by increasing fees and cutting our benefits,” says Bomar, who works as a research assistant while he pursues his PhD in biomedical engineering at the University of Maine. “Graduate school is already a very stressful and difficult experience, and universities owe it to their [graduate assistants] to protect their well-being.”

In addition to improving financial support for these workers, Bomar says universities can take other measures to better support graduate students. Providing free mental health counseling and making sure that people are aware of and encouraged to use these services would be “a golden tool” in reducing the chronic stress that many of these individuals contend with, Bomar says.

Transparent guidelines regarding assistantship appointments and work duties are another essential way to support their students, he says. Similarly, universities can encourage and train faculty advisors to “take a more holistic approach to training and teaching their students,” Bomar says.

“I think a lot of problems stem from a lack of communication between students and faculty,” he says. “A student who works 60-plus hours a week for too long could get totally burned out but may be afraid to go to their advisor about this because they feel that’s what is expected of them. That just leads to mental health problems and poor work performance.”

NAGPS has found that when graduate students communicate with their teachers and advisors about the stress they are under, faculty members are extremely receptive. They want to see their student workers succeed but may be unaware of their struggles, Bomar says.

“There’s this lingering culture that if you’re a graduate student, you should be miserable, because that’s part of the experience. If you’re working in a lab, you should be there all day and never go home,” he says. “That’s an old-school culture that serves nobody well.”

Mariah Bohanon is the associate editor of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in our June 2019 issue.