Naomi Rosenberg, MD, had just graduated from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University (LKSOM) when she decided to treat herself to a weeklong writers’ retreat. A former English major, Rosenberg says she wanted the opportunity to reflect on her recent experiences as a resident in a busy urban hospital. When given a writing prompt for an instructive essay, she jotted down the most difficult lesson of her medical training.

The resulting piece, “How to Tell a Mother Her Child Is Dead,” was later published in The New York Times and garnered responses from hundreds of physicians who could never forget their own experiences. “One guy wrote me about something he had said to a [deceased] patient’s family 60 years ago,” Rosenberg says. “Those experiences live on inside of us.”

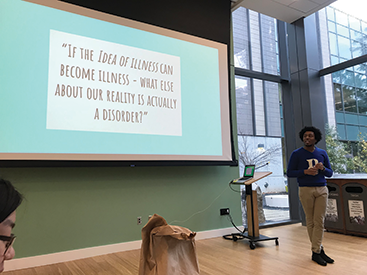

[Above: Jonathan Hill-Rorie teaches a Narrative Medicine Mondays session at Duke University’s Health Humanities Lab. A Duke alum, he studied narrative and mental health as a graduate student at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.]

Rosenberg now teaches narrative medicine at LKSOM, helping students and colleagues process their own experiences through storytelling. A relatively recent concept, narrative medicine applies the principles of reflective writing and literary analysis to humanize the often impersonal nature of modern healthcare. The goal is to provide better patient care with the added benefit of improving physician job satisfaction and reducing burnout.

Rosenberg now teaches narrative medicine at LKSOM, helping students and colleagues process their own experiences through storytelling. A relatively recent concept, narrative medicine applies the principles of reflective writing and literary analysis to humanize the often impersonal nature of modern healthcare. The goal is to provide better patient care with the added benefit of improving physician job satisfaction and reducing burnout.

Like many in this field, Rosenberg participates in ongoing trainings through Columbia University’s Division of Narrative Medicine, the first program of its kind. Intensive weekend workshops attract clinicians, writers, and educators from across the world. The division also offers an online certificate and a Master of Science program that enrolls people from multiple academic backgrounds and career fields. Medical students can take electives or even combine the degree with their clinical training.

Like many in this field, Rosenberg participates in ongoing trainings through Columbia University’s Division of Narrative Medicine, the first program of its kind. Intensive weekend workshops attract clinicians, writers, and educators from across the world. The division also offers an online certificate and a Master of Science program that enrolls people from multiple academic backgrounds and career fields. Medical students can take electives or even combine the degree with their clinical training.

Rita Charon, MD, PhD, the division’s executive director, first coined the term “narrative medicine” in 2000 after earning her English doctorate. As an internist and professor for Columbia’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, she had spent 10 years researching ways to apply critical reading skills in a clinical setting. “It was just stunning,” Charon says of her English degree. “I found that there was a one-to-one correspondence between what I was learning in class and what I was able to do with patients.”

Too often, medical training ingrains a singular focus on the body, dismissing other patient concerns as small talk, Charon says. English majors, however, are trained to understand the perspective of others and deduce meaning from tone, sentence structure, and other narrative elements.

“Physicians are trained to zero in as quickly as possible on the physical problem,” she says, but they can provide better care if they consider the patient’s experiences and connect with them.

Charon encourages students to practice what she calls “radical listening” by letting patients explain the “story” of their ailment, including details like the time, place, and emotions or events related to symptoms. She also urges physicians to write narratives of their interactions with patients. Known as parallel charts, these accounts may supplement official medical records or be shared with patients and colleagues. The practice can require as little as two to three minutes of jotting down an unofficial, subjective summary.

Charon encourages students to practice what she calls “radical listening” by letting patients explain the “story” of their ailment, including details like the time, place, and emotions or events related to symptoms. She also urges physicians to write narratives of their interactions with patients. Known as parallel charts, these accounts may supplement official medical records or be shared with patients and colleagues. The practice can require as little as two to three minutes of jotting down an unofficial, subjective summary.

These simple methods can be highly effective in improving patient-doctor relationships. Research shows that people are more likely to follow instructions from a physician who seems truly invested in their lives and empathetic to their concerns. Narrative medicine can also reduce bias and improve care for marginalized populations. “Radical listening is the effort to be present, to bear witness, and to listen without your biases and assumptions. It’s about curiosity, not judgment,” Charon says.

These simple methods can be highly effective in improving patient-doctor relationships. Research shows that people are more likely to follow instructions from a physician who seems truly invested in their lives and empathetic to their concerns. Narrative medicine can also reduce bias and improve care for marginalized populations. “Radical listening is the effort to be present, to bear witness, and to listen without your biases and assumptions. It’s about curiosity, not judgment,” Charon says.

Columbia engages in a number of research projects to explore narrative medicine’s potential for reducing health disparities. The program’s faculty — who come from both scientific and humanities backgrounds — make social justice a top priority. “This isn’t just about being a nice doctor or having a nice bedside manner,” Charon says. “It’s hearing and taking responsibility for improving access and equity, because it’s in our power to do this.”

Practicing narrative medicine techniques allows doctors to reconnect to their passion for helping others and process the emotional stress of working with the sick and dying — both of which are increasingly difficult given the structure of modern healthcare, Charon says. A recent workshop at Columbia addressed what Harvard Medical School’s Health Blog describes as the “severe and worsening epidemic of physician burnout.”

Students and physicians may believe they are too busy to learn or practice these techniques, but narrative medicine makes what little time doctors have with patients all the more valuable, says John Vaughn, MD, professor and director of student health services at Duke University School of Medicine. He explains this concept with a famous quote by William Osler, the father of modern medicine: “Listen to your patient. He is telling you the diagnosis.”

In addition to teaching a clinical elective on the subject, Vaughn co-hosts monthly classes known as Narrative Medicine Mondays. Sessions last less than two hours and involve discussion of a short story, poem, or film clip. “Whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, you’re taking on the point of view of another person,” Vaughn says, “which is one of the foundational purposes of narrative medicine and a foundational skill of being a physician.”

Participants may be asked to rewrite a medical narrative from the point of view of a patient or pen something more personal, such as describing a time they felt their own story was lost on a listener. “The key is to have them write for five minutes and then share exactly what they wrote with no editorializing or explanations,” Vaughn says. “That’s hard to do because it makes you feel very vulnerable.”

From there, they draw connections and gain new perspectives from each other’s narratives. The experience also helps them empathize with vulnerable patients who have to communicate with sometimes dismissive doctors in order to receive proper care, he says.

Narrative medicine has struck a chord with the medical community. Vaughn says a growing number of pre-med students have expressed interest in the discipline and more schools are introducing classes and programs in this area.

Perhaps the greatest indicator of the field’s popularity, however, is Charon being named the 2018 Jefferson Lecturer in the Humanities. Awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the recognition is the federal government’s highest honor for distinguished intellectual achievement in this field. NEH Chairman Jon Parrish Peede stated in a press release that Charon’s work “gets to the very core of the human condition.”

To learn more about narrative medicine and educational opportunities through Columbia University, visit narrativemedicine.org. Mariah Bohanon is the associate editor of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in our May 2019 issue.