Research shows that men have a key role to play in the advancement of women in STEM, as well as in all fields where women are underrepresented.

Roberta Rincon, PhD, in the Society of Women Engineers’ publication, SWE Magazine, says that “where men are the majority, their behaviors and actions are necessary to address inequities within their immediate spheres. … They also have the ability to serve as role models and spokespersons for other men.”

When men step up to address gender inequity, they help frame the issue as an organizational mandate rather than a so-called “women’s issue.” Male allies can also mitigate the personal and professional costs women sometimes experience when they advocate for themselves, Rincon says.

When men step up to address gender inequity, they help frame the issue as an organizational mandate rather than a so-called “women’s issue.” Male allies can also mitigate the personal and professional costs women sometimes experience when they advocate for themselves, Rincon says.

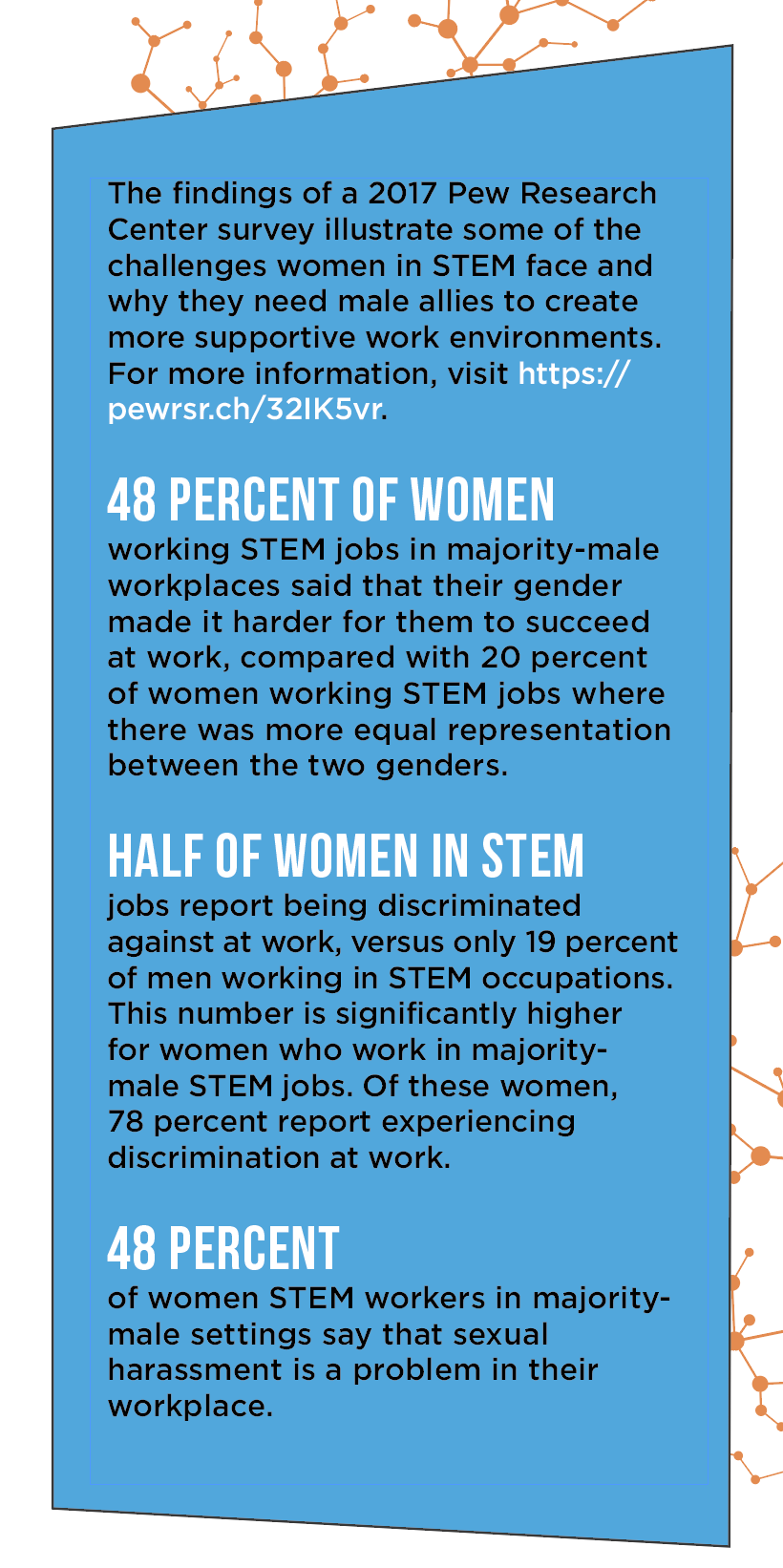

Implicit bias against female scientists is pervasive. It puts them at a disadvantage in numerous areas, from student evaluations to hiring decisions to formal recognitions and honors, among other forms of discrimination.

The inequitable climate toward women in STEM can discourage them from entering the field. Only 20 percent of American engineers are women, for instance, according to an article by Roger Green, PhD, and published by the American Society for Engineering Education.

To improve conditions, Green helps lead a prominent male allyship program at North Dakota State University (NDSU) called Advocates and Allies. NDSU launched it in 2009 after receiving an ADVANCE grant from the National Science Foundation.

Through the program, men work with other men — held accountable by women who review and approve any recommended actions — to learn how they can take both personal and institutional steps to make STEM departments more equitable for female scientists.

Through the program, men work with other men — held accountable by women who review and approve any recommended actions — to learn how they can take both personal and institutional steps to make STEM departments more equitable for female scientists.

Allies and advocates in the program have different roles. Allies participate in a two-hour training in which they learn more about gender inequity in STEM and gain practical skills for supporting their female colleagues. They are encouraged to create a personal action plan in order to put the training into action.

Advocates lead the ally trainings and meet monthly to evaluate ways to implement broader institutional change, then run these ideas by female colleagues. Advocates form a much smaller group, approximately 10 to 12 individuals.

Though advocates invest a significant amount of time in this work — including helping to expand the original NDSU program at 21 other institutions of higher education — it is crucial that they are not paid for their efforts, Green says.

Though advocates invest a significant amount of time in this work — including helping to expand the original NDSU program at 21 other institutions of higher education — it is crucial that they are not paid for their efforts, Green says.

“Women have been doing the hard gender equity work way longer than most men have. They aren’t recognized for it. They aren’t paid for it. In fact, they’re penalized for it. It’s a really bad idea to pay men to do this,” he says.

Advocates at NDSU have contributed to some important institutional initiatives, such as fighting for a university daycare to stay open. However, Green emphasizes the value of taking a grassroots approach. “It’s not all institutional change. Part of the reason we do the [ally] trainings is because I don’t think you can change systems unless you can change the people within the systems,” he says.

Nearly 90 percent of the men who participate in ally training either at NDSU or other participating universities report that they’ve learned something new and have gained skills to provide more gender equitable environments.

How to Be an Effective Male Ally

In developing the program, the leaders of Advocates and Allies have learned a great deal about what constitutes effective male allyship. Here are some of the action steps they encourage men in STEM to take:

● Review literature about gender inequity in STEM. Green recommends starting with the report “Engaging Men in Gender Initiatives: What Change Agents Need to Know,” which is available online at bit.ly/2Oc5uKe.

● Review literature about gender inequity in STEM. Green recommends starting with the report “Engaging Men in Gender Initiatives: What Change Agents Need to Know,” which is available online at bit.ly/2Oc5uKe.

● Assess your own implicit bias by taking a gender-science implicit association test, such as the one offered by Harvard University at implicit.harvard.edu/implicit.

● Investigate the gender representation within your own science department or program and compare it with the national statistics, available on the American Society for Engineering Education website.

● Serve on a hiring committee with the express purpose of being an ally for gender equality.

● Learn to recognize common forms of resistance to gender equity and plan effective responses. Green recommends the book Faculty Diversity: Removing the Barriers by JoAnn Moody, PhD.

● Be intentional about actively listening to women and redirecting the conversation toward them if they are interrupted. “Men are more likely to interrupt women when they speak compared to other men. Further [research] suggests that women are perceived as talking more than men when they talk only 30 percent of the time,” Green writes.

● Look for small, effective ways to improve the campus climate for women, such as inviting female colleagues to informal gatherings where work-related discussions may occur and sharing information equally between men and women.

● Advocate for a healthy work/life balance for both women and men.

● Promote and formally recognize research conducted by women.

● Tell your male colleagues about your role as a gender equity ally and treat instances of gender bias as teachable moments.

● For more tips, Green suggests watching the YouTube video “Five Ways Men Can Help End Sexism” (youtu.be/o1ZctJat4pU).

Most importantly, he urges STEM departments across the country to make men an integral part of the push for greater gender equity in the sciences. “You’re not going to change highly gendered organizations without involving the majority group,” he says.

Ginger O’Donnell is a senior staff writer for INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in the September 2019 issue.