As colleges and universities in the United States face persistent declines in both domestic and international enrollment, some institutions have redirected their recruitment efforts toward the diverse African continent.

The University of Rochester (Rochester), for example, began strategically recruiting students from Africa in 2010. Today, nearly 175 African undergraduates are enrolled at this elite university, according to Jennifer Blask, executive director for international admissions.

[Above: Left: Enky Mhlongo of South Africa (left) walks the University of Rochester campus with Princesse Mutesi Karemera of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (right).]

At Amherst College in Massachusetts, nearly 20 percent of international students are from Africa following significant recruitment efforts there that began in 2007, according to Xiaofeng Wan, Amherst’s associate dean of admission and coordinator of international recruitment.

This enrollment trend comes amid a downturn in applicants from the Asian countries that have traditionally been the most popular sources of international students for the U.S. Nearly half of American colleges and universities experienced declines in Chinese student enrollment last year, as reported in the December 2019 issue of INSIGHT. Enrollment of new students from India dropped at 40 percent of institutions, according to a fall 2018 report from the Institute of International Education (IIE).

Meanwhile, enrollment from African nations has risen steadily since the 2015-2016 school year, increasing by several percentage points annually. In 2018-2019, nearly 40,300 African students attended U.S. colleges, according to IIE.

Increases in African Enrollment

Demographics across Africa have created ripe conditions for such a shift. The continent is experiencing a “youth bulge,” with the median age in Sub-Saharan Africa being 19.5 years, according to a recent NAFSA: Association of International Educators (NAFSA AIE) article. Furthermore, the tremendous growth in the 18-to 25-year-old population is projected to continue over the next 30 to 50 years, says Rachel Banks, NAFSA AIE’s director of public policy.

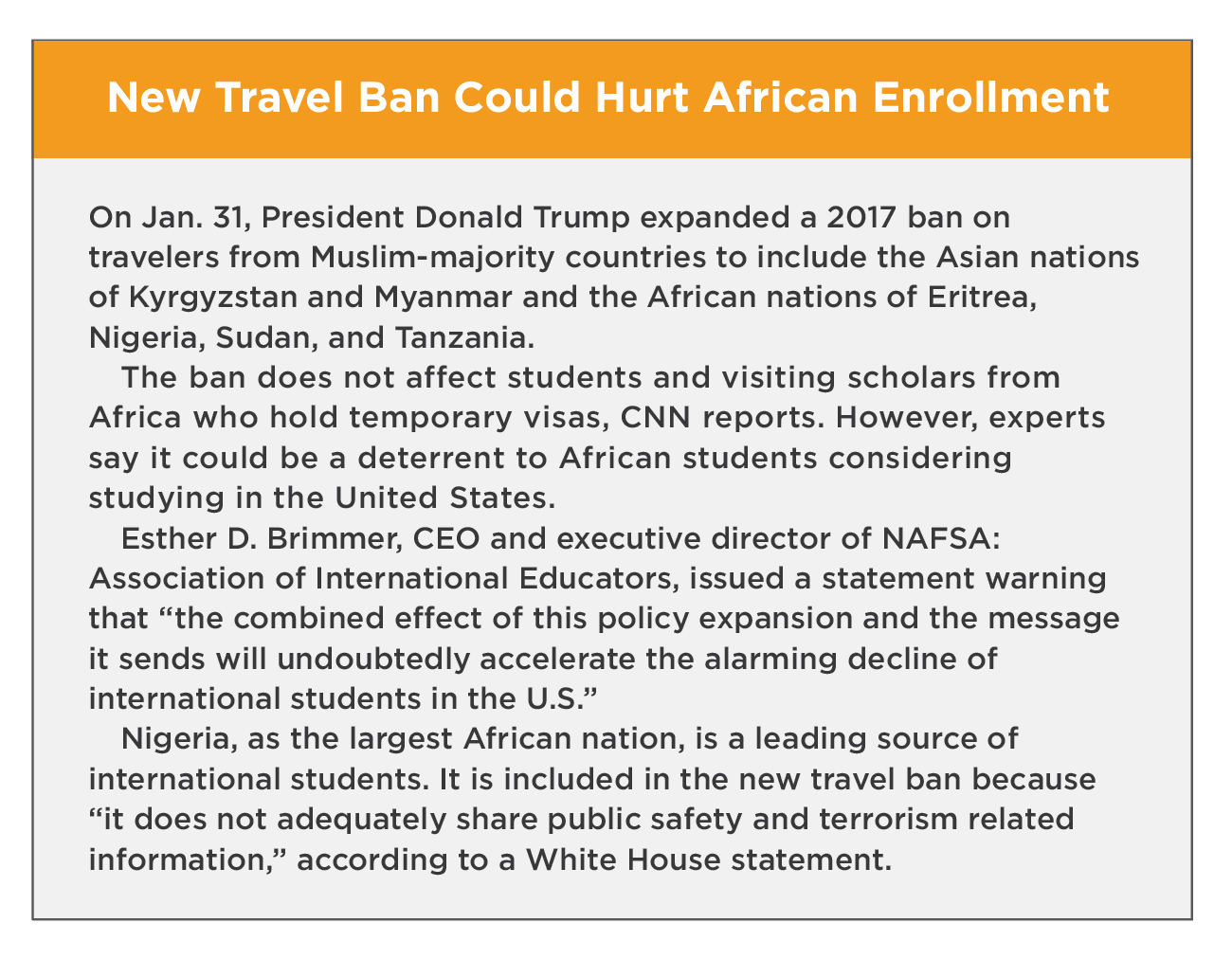

In Nigeria, 60 percent of the population is under the age of 25. Yet its struggling higher education sector has failed to keep up with demand, with 38,000 qualified applicants being turned away from universities in 2017. The country’s growing middle class has had to look elsewhere for college degrees, resulting in a 164 percent increase in Nigerian enrollment in U.S. institutions between 2005 and 2015 alone, according to World Education Services.

In Nigeria, 60 percent of the population is under the age of 25. Yet its struggling higher education sector has failed to keep up with demand, with 38,000 qualified applicants being turned away from universities in 2017. The country’s growing middle class has had to look elsewhere for college degrees, resulting in a 164 percent increase in Nigerian enrollment in U.S. institutions between 2005 and 2015 alone, according to World Education Services.

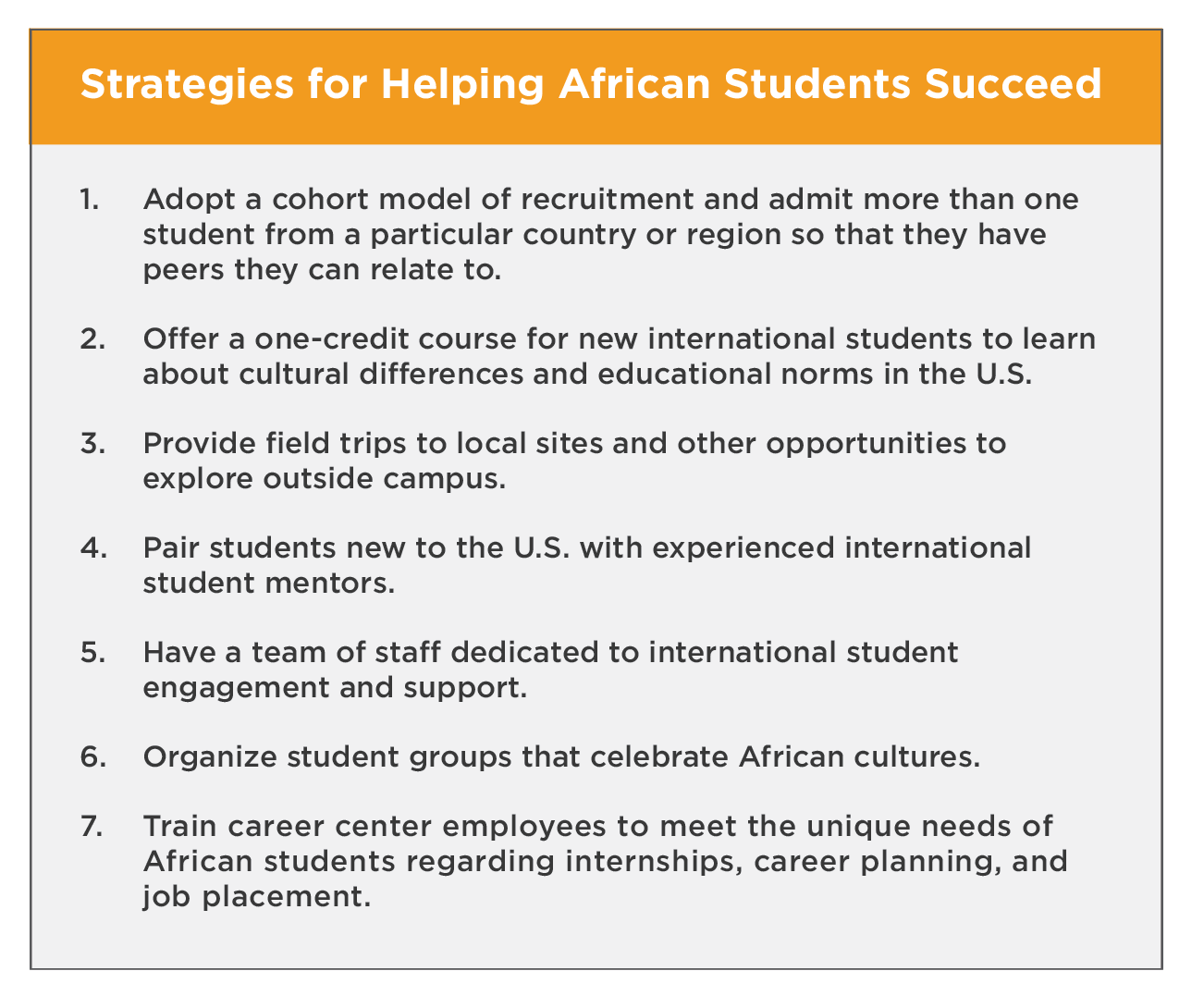

Amherst and Rochester both say they seized the opportunity to recruit from Africa’s growing youth population because they wanted to enrich the diversity of their campus communities.

Amherst’s decision was motivated in part “to prepare students for an increasingly global, interconnected world,” says Matthew McGann, EdD, dean of admission and financial aid. “[We] wanted to bring in individuals that represent not just the diversity of the country, but the diversity of the world.”

At Rochester, recruitment officials realized that “having only a few students from Africa on our campus” was a missed opportunity for exposing domestic and other international students to more diverse cultures and perspectives, Blask says. Recruits from Africa have “really changed the campus culture” as their numbers have grown in recent years, she says.

They also tend to be extremely high-achieving students and alums. “We have success story after success story from our African students who go on to prestigious fellowships, graduate programs, and companies, who then go back and really change the face of the communities that they’re from,” Blask says.

Challenges

Despite the tremendous opportunity that exists in Africa and the value that these students bring to American campuses, recruiting within the continent poses significant challenges.

One barrier for African students is the U.S. standardized admissions tests. Access to ACT and SAT testing centers can be extremely limited in African nations, with some students having to travel to other countries to take these exams. While a growing number of U.S. institutions are test-optional, those that still require the ACT or SAT can make the admissions process more equitable for African students by accepting scores from comparable exams that are more familiar to international students.

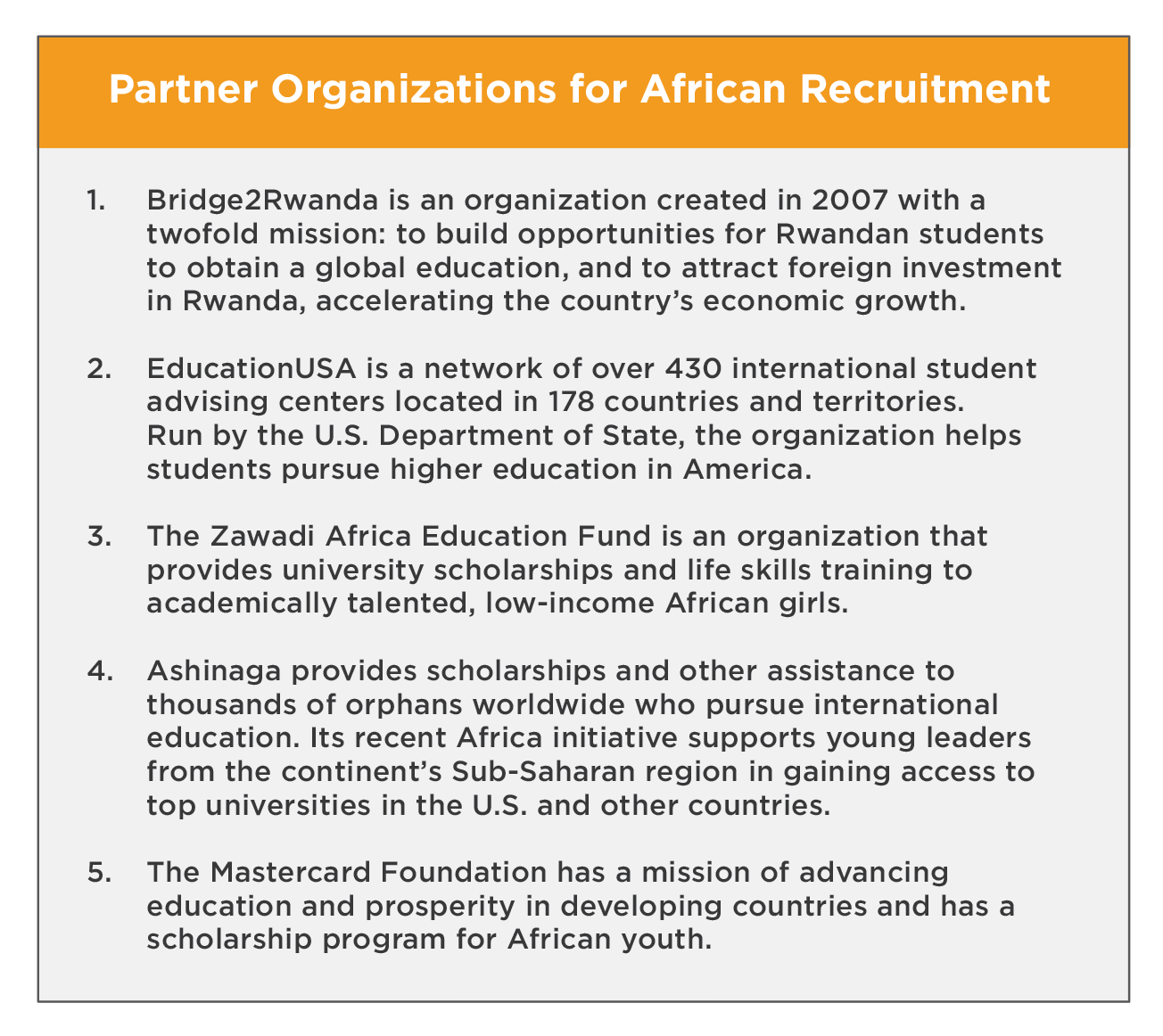

Amherst, which has an overall acceptance rate of 13 percent, uses a holistic admissions model that takes into account which scores are considered competitive in different regions of Africa, according to McGann. Rochester no longer requires the ACT and SAT, but McGann notes that partner groups such as EducationUSA can assist African students in accessing these tests if necessary.

The continent’s size and linguistic diversity also create challenges for American recruiters. Many colleges rely on partner organizations such as the African Leadership Academy (ALA) to identify potential students. Located in South Africa, ALA prepares high-achieving high school juniors and seniors from across the continent to succeed in college both domestically and abroad.

The continent’s size and linguistic diversity also create challenges for American recruiters. Many colleges rely on partner organizations such as the African Leadership Academy (ALA) to identify potential students. Located in South Africa, ALA prepares high-achieving high school juniors and seniors from across the continent to succeed in college both domestically and abroad.

ALA and other partners “have allowed us to find really strong, high achieving students who are vetted and able to provide us with their verified documentation” to attend school in the U.S., Blask says, noting that gaining access to proper travel and study credentials can also be difficult for students in some African countries.

In addition, some nations have limited infrastructure when it comes to physical roads and internet access. One solution for recruiters is to attend regional conferences on the continent where “you can see lots of great schools and community organizations all in one place,” Blask recommends.

Groups such as the High-Achieving Low-Income Access Network (HALI), an umbrella organization for groups working to improve African student access to international education, tend to organize these events. HALI also provides contact information for all of its partner organizations online, making it easy for college recruitment staff to connect with resources in Africa, Blask says.

Groups such as the High-Achieving Low-Income Access Network (HALI), an umbrella organization for groups working to improve African student access to international education, tend to organize these events. HALI also provides contact information for all of its partner organizations online, making it easy for college recruitment staff to connect with resources in Africa, Blask says.

A major barrier for institutions that want to grow African enrollment is cost. Wan says it can be difficult for many African students to come up with what might seem in the U.S. like relatively small amounts of money. He encourages any institution considering recruitment in Africa to have enough funding “to meet 100 percent of demonstrated need for these students before doing anything within the continent.”

Amherst and Rochester each account for these costs under their financial aid policies, as both schools cover all demonstrated need for domestic and international students. Amherst also has a scholarship fund for African and Latin American students, which pays for its admissions team to work two weeks a year in Africa.

When it comes to making the case for investing in African student recruitment, Blask recommends starting small, such as engaging virtually with potential partner organizations. As enrollment builds, she says, campus leadership should see the value these students bring academically and culturally and realize the tremendous return on investment.

When it comes to making the case for investing in African student recruitment, Blask recommends starting small, such as engaging virtually with potential partner organizations. As enrollment builds, she says, campus leadership should see the value these students bring academically and culturally and realize the tremendous return on investment.

Ginger O’Donnell is the assistant editor of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in the March 2020 issue.