Vincent C. Flewellen, the chief diversity officer for Webster University in St. Louis, had a turbulent start to 2019.

In December last year, NBC News interviewed Flewellen for a nationally broadcast feature on “White spaces,” or discussion groups and workshops for White people to reflect on their racial identities, biases, and assumptions in order to become more proactive anti-racism advocates.

The backlash was severe.

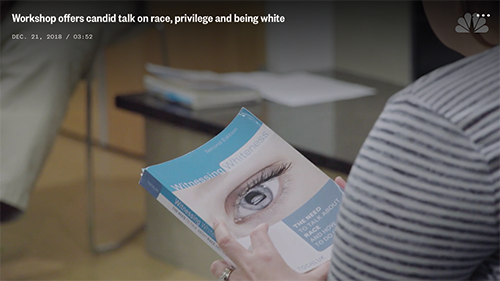

[Above: Tochluk’s book Witnessing Whiteness: The Need to Talk About Race and How to Do It serves as a guidebook for White allies participating in a racial awareness workshop. (NBC News screenshot)]

Flewellen and Patrick Giblin, Webster’s director of public relations, received a deluge of phone calls and emails criticizing the prospect of introducing this type of program to a college campus. Close to 30 news outlets, primarily far-right publications, picked up the story, Giblin says.

Websites such as Breitbart and Campus Reform referred to the program as a “segregated safe space” for participants to come to terms with their inner racism while a Wisconsin radio station described it as “demonizing” White students. Far-right website The New American deemed it a “reeducation camp.”

Much of the coverage contained erroneous details, such as stating that the program would be offered as a class for students rather than a workshop series for faculty and staff, or that Flewellen was also responsible for introducing a White spaces program at Washington University in St. Louis.

Such vitriol towards the concept of examining Whiteness as a racial construct is hardly new, however. State representatives in both Arizona and Wisconsin have tried unsuccessfully to ban certain ethnic studies courses after universities in their states began offering classes titled “The Problem of Whiteness.” In 2018, a new Whiteness studies course at Florida Gulf Coast University was guarded by two campus police officers on the first day of class after a professor received multiple threatening emails and phone calls.

Such vitriol towards the concept of examining Whiteness as a racial construct is hardly new, however. State representatives in both Arizona and Wisconsin have tried unsuccessfully to ban certain ethnic studies courses after universities in their states began offering classes titled “The Problem of Whiteness.” In 2018, a new Whiteness studies course at Florida Gulf Coast University was guarded by two campus police officers on the first day of class after a professor received multiple threatening emails and phone calls.

Vanderbilt University professor Jonathan Metzl was interrupted by a group of White supremacists in April while giving a presentation on his book Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland. In a column in The Washington Post, he wrote, “For too long, many white Americans have avoided this conversation, and we’ve done so for a reason: We don’t have to see the color white. Race scholars often argue that white privilege broadly means not having to reflect on whiteness.”

Yet the concept is gaining ground. In White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Race, diversity trainer and scholar Robin DiAngelo argues that Whiteness as a race must be addressed in order to advance racial justice. As a White woman, she calls on White people themselves to do the work of dismantling racism. The book became a New York Times bestseller in 2018.

This responsibility on the part of White allies is also the premise of Witnessing Whiteness: The Need to Talk About Race and How to Do It by Shelly Tochluk, PhD, professor of education at Mount Saint Mary’s University in Los Angeles.

This responsibility on the part of White allies is also the premise of Witnessing Whiteness: The Need to Talk About Race and How to Do It by Shelly Tochluk, PhD, professor of education at Mount Saint Mary’s University in Los Angeles.

Being a White ally requires awareness of the “political, economic, sociocultural, and legal histories that shaped the meanings associated with whiteness,” Tochluk’s website states. It also requires White readers to reflect on how they have benefited from racial privilege and how their own assumptions and attitudes about race have shaped their thinking and interactions with people of color, Tochluk says.

While critical Whiteness studies as an academic subject has existed as a subgenre of race studies for several decades, Tochluk emphasizes that her work does not examine Whiteness through an academic lens. As a former teacher in a diverse K-12 school and a student of psychology, she was inspired to write the book in 2007 as a practical guide for White educators and other allies seeking to understand “what it means to be a White person who is conscious of race and has taken up the responsibility to do something about it,” Tochluk says.

Tochluk’s book is intended to help readers realize that “we’re actually more influenced by racism than we think,” she says. White readers are guided into recognizing systemic discrimination, their own unconscious biases, and the ways in which they personally benefit from White privilege. Lastly, the book addresses how to use newfound awareness to become a more conscientious, self-aware ally — one who can help share these lessons with the White community.

The concept of creating a “White space” for this type of work may seem contradictory, but there are several imperatives behind this decision. Reasons include the premise that people of color should not always have the full responsibility to educate others about racism and should not have to be subject to “further undue trauma or pain as [White participants] stumble and make mistakes” during candid discussions, according to the Alliance for White Anti-Racists Everywhere-LA (AWARE-LA), an organization that helped Tochluk develop her workshop series.

Furthermore, Witnessing Whiteness programs are intended as a supplement to, not a replacement for, multiracial discussions and efforts to combat racism, according to AWARE-LA.

“I think White people are increasingly hearing the call that we actually need to educate each other and not depend on people of color to be our educators,” Tochluk says. “That doesn’t mean that we don’t also have multiracial conversations, but hopefully when we do enter multiracial dialogues, we do so more effectively and without being too dependent on [people of color] for validation.”

Community groups nationwide, including the St. Louis chapter of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), have hosted such workshop series since 2008. The demand for this type of program increased following the 2014 shooting of African American teenager Michael Brown, Tochluk says.

It was at this time that Flewellen first contacted the YWCA Metro St. Louis about bringing the program to the private K-8 school where he was then working. Many White parents and teachers had been asking for this kind of opportunity, and the program led to unique anti-racism education efforts within the school, he says.

Flewellen notes that the YWCA Metro St. Louis provides trained, White facilitators to lead the program for schools, churches, and other groups who request it. The format and materials are based on those developed by Tochluk and AWARE-LA.

In June, the Webster University administration gave Flewellen full approval to move forward with bringing the Witnessing Whiteness series to campus. A pilot program for faculty and staff will launch in fall 2019. “As a result of the publicity we received in December and January, there were faculty and staff members already asking when we were going to start the program,” says Flewellen.

In June, the Webster University administration gave Flewellen full approval to move forward with bringing the Witnessing Whiteness series to campus. A pilot program for faculty and staff will launch in fall 2019. “As a result of the publicity we received in December and January, there were faculty and staff members already asking when we were going to start the program,” says Flewellen.

Both Flewellen and Giblin say that despite the backlash, having the support of their university as well as allies who called or wrote to them from across the U.S. made this experience a positive one. “We spent about two weeks receiving hateful messages,” Giblin says, “but in the end we were able to make some great connections that are going to help us offer even better diversity and inclusion programs than we had before.”

Mariah Bohanon is the associate editor of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in the July/August 2019 issue.