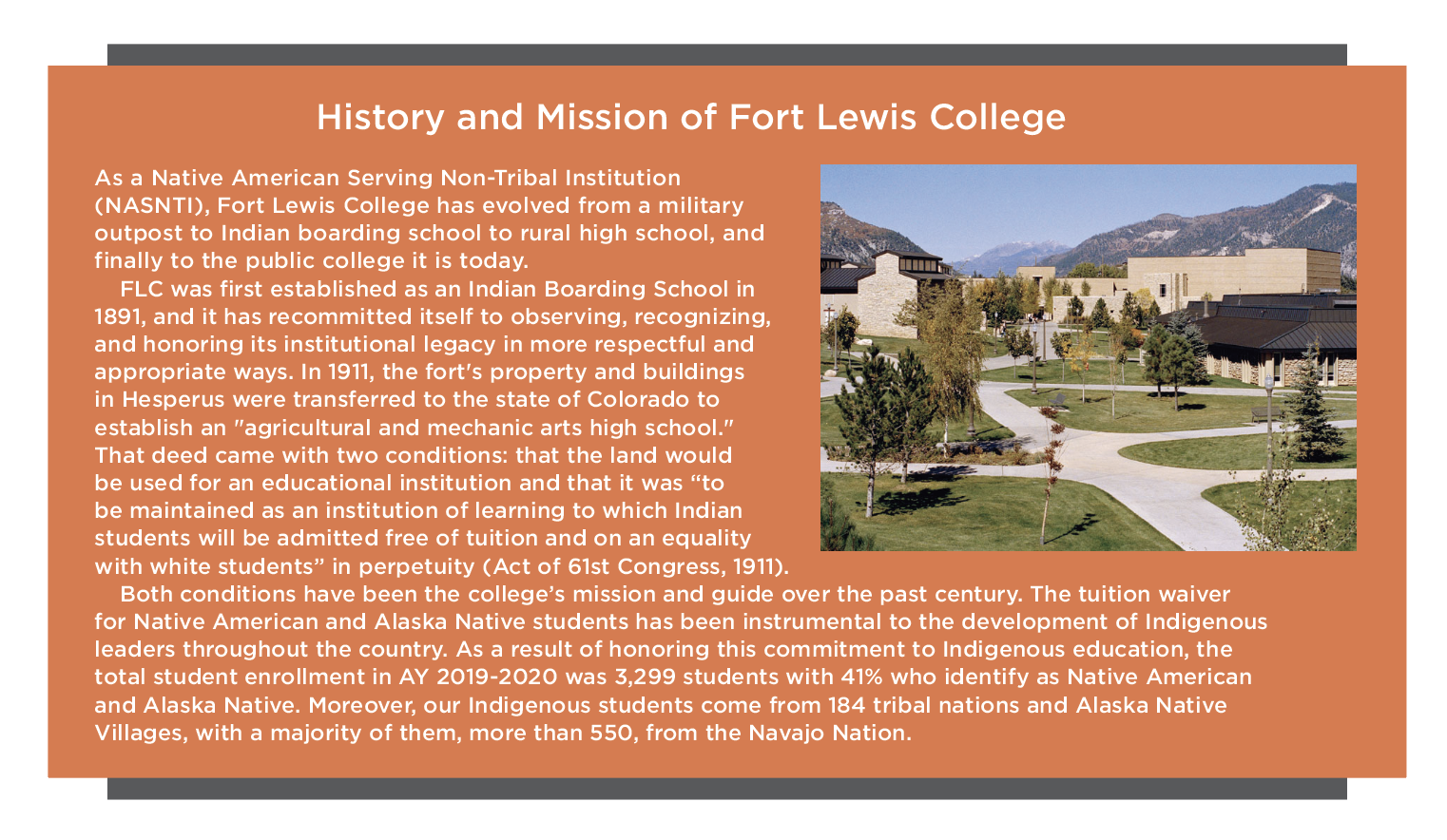

For Indigenous students, the struggles of campus closure and online learning are exacerbated by a severe digital divide. At Fort Lewis College — where four in 10 students are Native American or Alaska Native — administrators, faculty, and staff created a system of personal connections to meet individual technology needs.

Like other colleges and universities throughout the country, Fort Lewis College (FLC) in Durango, Colorado, transitioned rapidly to online classes in mid-spring. The exodus of students from campus refocused a light on the undeniable deficiency in access to education due to the digital divide — a big gap that resurfaced for many Indigenous students as they had to leave campus.

To fulfill our institutional mission of serving this student population, FLC created an individualized outreach campaign involving a team from our Native American Center and our faculty to personally contact every Indigenous student (via cell phone, text, and email) to support the successful completion of their courses remotely by understanding their specific needs and devising individualized solutions.

We discovered that many indigenous students faced similar difficulties when it came to the digital divide, including the following:

We discovered that many indigenous students faced similar difficulties when it came to the digital divide, including the following:

● Unavailable or unreliable internet access, which leads to struggles with daily assignments, communicating with faculty, synchronous coursework, and so on

● Lack of regular access to personal computers because they are shared with other family members — siblings taking classes or parents working remotely, sometimes at conflicting times — or because of outdated technology

● Lack of smartphones or phones in general because of budget constraints

● Lack of space or time for classes

● Familial responsibilities such as assisting with child care or elder care

● A return to uncertain home environments

● Newly imposed conditions in home environment — shelter at home orders, economic effects, and need for home schooling

● Decision not to return home but to live with urban relatives to have internet access

● Minimal to no support or encouragement to complete course work

● Combined impact of these issues on emotional, physical, and mental health

Our individual approach allowed us to provide targeted solutions by connecting students with specific services to address their technology needs and, when applicable, other services (e.g., advising, counseling, TRIO, information technology, and financial aid) that would support their success.

Most students we spoke with were appreciative and optimistic after we touched base with them. Addressing the fundamental issue of access to technological resources reduced or eliminated many other issues resulting from that deficiency. Many of these students were able to finish the semester successfully despite these new and challenging circumstances where there is a heavy requirement of connectivity and technology.

As a result of this unprecedented situation and our personal discussions with students, we learned several key concepts.

● Not all students (Native American/Alaska Native and other groups) have access to reliable internet connectivity and computer technology, so we are exploring how we can require all students to invest in a laptop and a means to connect.

● Thus, exploring how to include a technology bundle in the cost of attendance to ensure that this expense will be covered by financial aid — grants and scholarships or loans — is warranted.

● Thus, exploring how to include a technology bundle in the cost of attendance to ensure that this expense will be covered by financial aid — grants and scholarships or loans — is warranted.

● Students appreciated being contacted individually and directly, as it adds a personal touch and gives them a sense of importance and visibility. Hence, in an online environment, scheduling regular touch points so that students are even more aware that we are invested in their success is powerful.

● Given that we were able to strategize and create an outreach plan — in a short amount of time in collaboration and coordination with various offices and programs — we are exploring opportunities to use our collegiality and leverage resources to collaborate in the future for ongoing outreach to all students, especially students who are first generation or low socio-economic status, to work toward increasing retention and graduation rates.

● We were able to identify effective and powerful services and referrals that can continue into the future and align with our strategic core values as an institution — with “students at the center.”

● Examples include ensuring technology and internet access when possible, assisting in connecting with faculty, and providing information based on individualized needs of available resources, such as our Skyhawk Emergency Fund for financial hardship.

Accordingly, in planning to return to campus this fall, we are sharing this information with faculty to contemplate, discuss, and discover solutions for how to develop richer and more robust course offerings online; we may be considering hybrid formats and approaches for delivering our degree programs. We are also reimagining tactics for how to provide future advising, mentoring, coaching, and communication by including the emergent themes that we discovered in our conversations with students, and we welcome and value their input. We are proud of our collective efforts and believe that they will bode well for our Indigenous students during these trying times as well as into the future.●

Lee Bitsóí, EdD, is the director of the Diversity Collaborative and the Special Advisor to the President for Native American Affairs at Fort Lewis College. He is also a member of the INSIGHT Into Diversity Editorial Board. This article was published in our July/August 2020 issue.