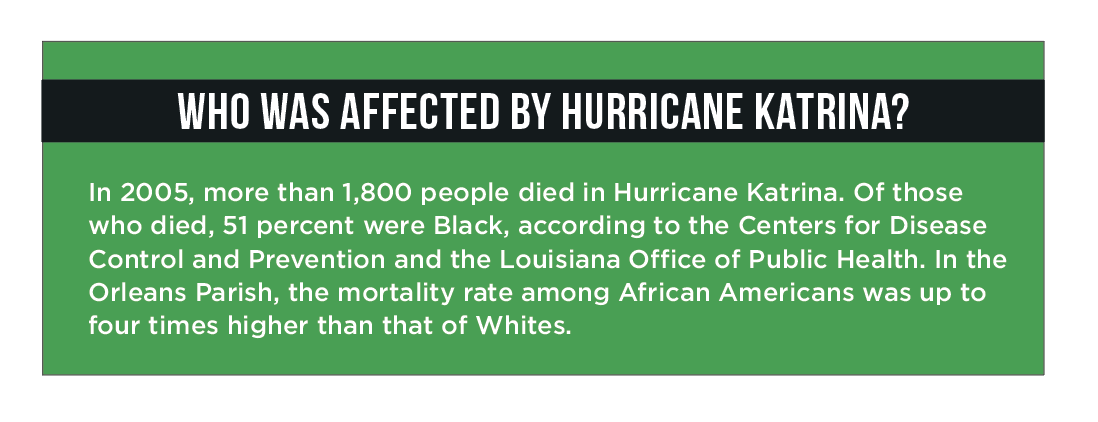

The impact of climate change hits politically, socially, and economically disadvantaged communities first and hardest.

After a decade of recession in Puerto Rico, where almost half the population lives below the poverty line, Hurricane Maria resulted in over 3,000 fatalities. The disaster left more than a million people without power or adequate resources.

[Above: Members of the Vermont Law School (VLS) Environmental Justice Law Society pose with VLS honorary degree recipient Mustafa Santiago Ali (third from left, top row) and VLS professor Rachel Stevens (far left) at an environmental justice conference in 2019. (Photo courtesy Vermont Law School)]

More than a year after flooding from Hurricane Harvey devastated the Houston area in 2017, causing over $125 billion in damage, three in 10 Texas Gulf Coast residents say “their lives remain disrupted,” according to the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Episcopal Health Foundation. Black and Hispanic residents and those with lower incomes were more likely to report being affected by the hurricane.

“One year later, many of those with the fewest resources are still struggling to bounce back from Harvey’s punch,” Elena Marks, president and CEO of the Episcopal Health Foundation, said about a 2018 study on the hurricane’s impact.

A 2018 special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations body for assessing the science related to the issue, found climate change has a bigger impact on the following groups: coastal communities, Indigenous groups, agriculture-dependent areas, elderly, disabled, impoverished, people of color, and women. Reducing global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared with 2 degrees Celsius “could reduce the number of people both exposed to climate-related risks and susceptible to poverty by up to several hundred million by 2050,” according to the panel’s report.

Environmental justice lawyers are among the strongest advocates for underrepresented communities affected by disasters such as Hurricanes Harvey or Maria.

As the effects of climate change worsen, the need for lawyers in this field grows. Law school administrators and students across the country have responded, says Jennifer Rushlow, PhD, associate dean for Environmental Programs at Vermont Law School.

“The environmental community has been very slow to widen the umbrella to include more than just the traditional, male-led, White efforts on national resources conservation,” Rushlow says. “I believe the movement will fail if it doesn’t change.” But students at Vermont Law and at law schools nationwide are “a force to be reckoned with,” she adds.

Practical application of theories learned in the classrooms is the most effective method for preparing students to help underrepresented communities, says Roger Lin, PhD, clinical supervising attorney at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) School of Law Environmental Law Clinic.

The clinic, Lin says, is “basically a law firm” that employs students to represent environmental justice groups across the state. “They get to experience every single aspect of the case,” he adds.

Practical experience prepares graduates to jump directly into working on international climate negotiations, developing federal policy, or advocating for communities on the local level, says Lisa Benjamin, PhD, a professor in the Environmental, Natural Resources, and Energy Law Program at Lewis and Clark Law School.

Practical experience prepares graduates to jump directly into working on international climate negotiations, developing federal policy, or advocating for communities on the local level, says Lisa Benjamin, PhD, a professor in the Environmental, Natural Resources, and Energy Law Program at Lewis and Clark Law School.

“Lewis and Clark students are very civic-minded,” Benjamin says. “A number end up at [non-government organizations], working with community organizations where they’re able to rectify wrongs or are able to be involved in policy formation.”

Increasingly, law school students are not only interested in advocating for underrepresented communities, but they’re also beginning to reflect those communities, says Rushlow, who is also acting director of Environmental and Natural Resources Law Clinic. Twenty-three percent of students at Vermont Law are people of color, and 57 percent are women.

“We have a lot of student leadership from our students of color. They want to see environmental issues addressed that impact them,” Rushlow says. “People of color care about the environment, and they care about protecting their communities. Any assumption that’s not the case is incorrect. … It’s time for the movement and for the academy to do its part in fostering leadership and building skills.”

Making Change Well Before Graduation

Lin’s students in the UC Berkeley Environmental Law Clinic achieved a big win recently, well before they had earned their law degrees. They successfully fought for and won $60 million in pilot projects for 11 communities in the state’s Central Valley that don’t have access to reliable electricity.

Allensworth, Calif., is one of those communities. Founded by Lt. Col. Allen Allensworth, a Black man born into slavery who escaped to join the Union army, it became known as the first African American town to be established after the Civil War.

While the town was created with the idea that Black citizens could pursue their own American dream, Allensworth became “redlined out of investment,” Lin says. The state didn’t pay for infrastructure there, and over time, residents turned to other means for energy. Still today, the few hundred people living there, most of whom are African American, use wood and propane to heat and cool their homes. Extreme weather swings in the Central Valley connected to climate change are making things worse.

While the town was created with the idea that Black citizens could pursue their own American dream, Allensworth became “redlined out of investment,” Lin says. The state didn’t pay for infrastructure there, and over time, residents turned to other means for energy. Still today, the few hundred people living there, most of whom are African American, use wood and propane to heat and cool their homes. Extreme weather swings in the Central Valley connected to climate change are making things worse.

Students in the Environmental Law Clinic helped amplify residents’ voices. State assembly bill 2572 ordered the California Public Utilities Commission to investigate ways to provide affordable energy to communities such as Allensworth, of which there are 170 statewide. Lin says he hopes solutions can be replicated in the other 159. Most of the pilot projects include solar options for power.

“You do need a lawyer for every single step to work closely with residents to make sure we get their opinions and uplift their voices,” Lin says. “It’s really important for the role of the lawyer to be a guide for the residents, for folks who don’t understand the legal system, to open doors for them, to translate all the technical terms.”

At Lewis and Clark Law, the Green Energy Institute and the International Environmental Law Project provide practice in applying the law in real-world situations. Recently, students in the institute worked with local county officials to reduce carbon emissions from diesel trucks, Benjamin says. People who cannot afford healthcare for illnesses caused by poor air quality are at an inherent disadvantage.

“The reason they are so highly impacted is because socially, politically, economically, they are disadvantaged already,” Benjamin says. “Environmental issues are mediated through these social structures as disadvantages, and the vulnerable are impacted more.”

Next year, Vermont Law plans to launch an Environmental Justice Clinic where students will work with community groups nationwide to address policy issues. The new effort will complement the existing Environmental and Natural Resources Law Clinic, which allows students to serve as the lead attorney in environmental cases under the supervision of an experienced lawyer.

Trends in Environmental Justice Cases

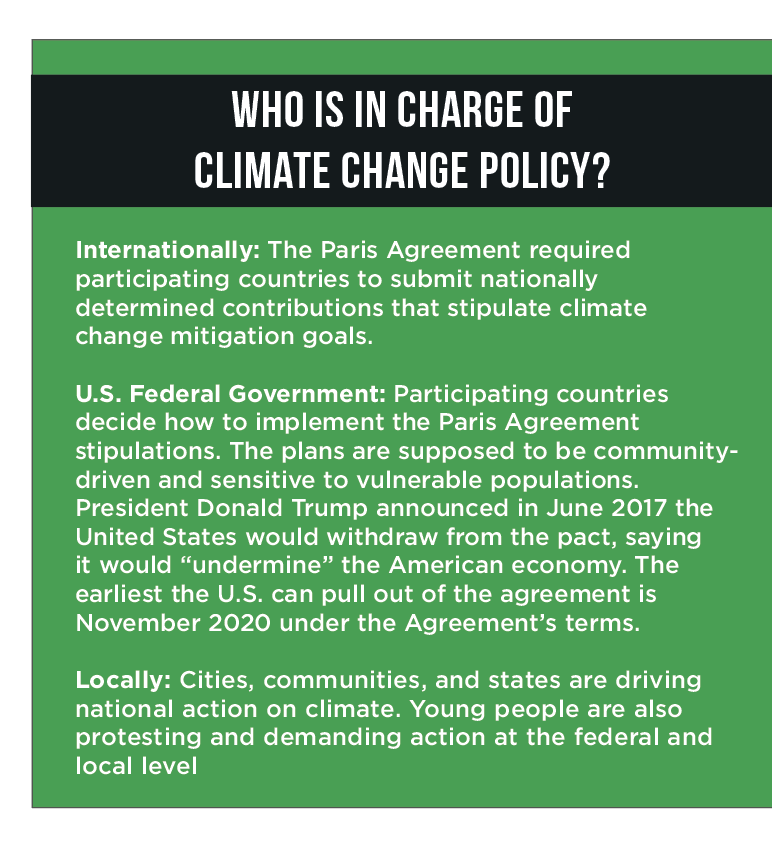

One of the exciting trends in environmental law is youth bringing litigation to challenge government inaction, Rushlow says. As part of a 2016 case in Massachusetts, Rushlow helped four teenagers sue the Department of Environmental Protection to force them to uphold regulations in the state’s Global Warming Solutions Act. The state’s highest court ruled in the teens’ favor, forcing the state to do more to reduce emissions.

Juliana v. United States is another lawsuit brought by a group of young people. In 2015, they claimed under the Public Trust Doctrine that the federal government violated their constitutional rights by allowing dangerous levels of carbon dioxide to develop. The case continues in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, headquartered in San Francisco.

Juliana v. United States is another lawsuit brought by a group of young people. In 2015, they claimed under the Public Trust Doctrine that the federal government violated their constitutional rights by allowing dangerous levels of carbon dioxide to develop. The case continues in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, headquartered in San Francisco.

“The concept is that the government holds public resources in trusts for the public,” Rushlow says, and by failing to control atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, they have endangered the lives of children.

Lin says he hopes to see more cases like these. “Court cases can make a big splash,” Lin says. “As long as it keeps pushing the movement forward, I very much hope that it does [continue to happen].”

As climate change continues to make conditions more extreme, especially for people in underrepresented communities, environmental justice attorneys trained with practical experience in law school will become all the more important, Lin says.

“Students meet the families whose lives are going to be changed by these projects,” Lin says.

“They’re seeing every aspect from start to finish and in the real world.”

Kelsey Landis is the editor-in-chief of INSIGHT Into Diversity. This article ran in the July/August 2019 issue.