Projects Reframe Conflict as Opportunity

While the proverbial halls of higher education are rife with hard conversations and debate involving moral, political, and social topics, these are all part of the learning process. Therefore, when conflict arises in the classroom, on campus, or among friends and others, it should be seen not as a roadblock but as another opportunity to explore and learn from diverse perspectives.

Two academic initiatives seek to reframe conflict as a positive force. One works with students on how to navigate conflict in difficult discussions and the other trains faculty and staff to engage students in productive political dialogue. These projects provide the campus community with the particular skills required to participate effectively and persuasively in difficult discussions.

With a $25 million grant from an anonymous donor, Middlebury College launched the Kathryn Wasserman Davis Collaborative in Conflict Transformation (CCT) last spring. The program teaches students the concept that conflicts are never over — they merely change form — so the best solution is to move an issue to a productive and more peaceful dynamic.

At Tufts University, the Institute for Democracy & Higher Education (IDHE) has created guidelines for faculty and staff around engaging in politically charged discussions with students.

With increased political polarization across the country, it’s an important moment for conflict transformation work, says Sarah Stroup, PhD, executive director of the CCT and professor of political science at Middlebury.

“Social change requires working with folks who might not be exactly like you but on an issue of concern you are on the same page, even if on other issues you might have disagreement,” she says.

Developing Conflict Transformation Skills

The CCT is a wide-ranging initiative that educates students at the high school, undergraduate, and graduate levels through global curricula and experiential learning opportunities.

Students learn critical self-awareness, how to gain contextual knowledge around an issue, and how to communicate across differences.

They also learn mediation skills and restorative practices that focus on how communities can be held accountable for harm done to a group of people, allowing those who were harmed to tell their story and bringing the victim and offender together to restore their relationship.

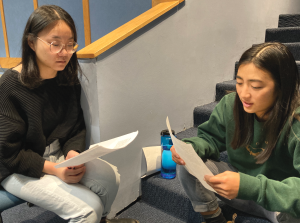

(Photo courtesy of Middlebury College)

One of the first exercises undergraduates practice, with a classmate, is resolving an interpersonal conflict. They repeat back their understanding of the conflict to each other until they get it right. Students also practice conversational receptiveness — the use of particular language that signals openness to hearing something contrary to their own perspective. In meaningful ways, students are able to shift the dynamics of interpersonal conflicts where they’re stuck, Stroup says.

“I am quite confident that we are able to, in our classrooms and on our campuses, engage in deep and complex discussions about enormous social problems and ambitious and challenging ideas,” says Stroup.

Guidelines for Political Discussions

Nancy Thomas, JD, EdD, director of IDHE, provides guidelines for faculty and staff on how to facilitate discussions regarding controversial issues focused on democracy, in her report “Readiness for Discussing Democracy in Supercharged Political Times.”

One of the most important messages in her guide, she says, is that remaining neutral in a discussion isn’t always possible if it disrupts education, creates stressful or toxic environments for students from historically marginalized groups, or perpetuates misinformation.

Oftentimes, faculty are afraid of being accused of censorship, yet it’s important sometimes to draw the line.

“[For example,] there’s no evidence to support that the election was stolen,” says Thomas. “What do you do? Do you let that opinion just be part of a process of conversation? Or do you say, ‘We’re going to correct the record, and then we’ll go on’?”

This is also a lesson for administrative leaders, she says. Legally, the four essential freedoms of a university are determining on academic grounds who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study. Although there are limitations to academic freedom, Thomas feels institutions should consider intervening to a greater extent when these freedoms are jeopardized, such as in situations that promote hate speech.

Oftentimes, faculty are afraid of being accused of censorship, yet it’s important sometimes to draw the line.

“My position is that we also have obligations to historically marginalized groups or people who are often the target of hate speech or discriminatory learning conditions,” Thomas says. “I think there needs to be a recalibration of that.”

For productive political discussion to take place among faculty and students on campus, Thomas offers guidelines.

Establishing agreements that lay out expected behaviors in group discussions are critical, especially those that prohibit personal attacks or intimidation. Agreements can also facilitate open-mindedness, risk-taking, and listening.

Inquiry and asking for clarification helps to advance critical and analytical thinking, and fosters discussion goals. But silence can also be used as a listening strategy and to draw out new perspectives.

For this to work, however, it’s essential to first promote a culture of cooperation and shared responsibility. Often, this can be accomplished by allowing students to work together in small groups so they can get to know each other and find common experiences or traits.

“We share responsibility on college campuses for each other’s success, for each other’s well-being,” Thomas says. “That’s what ‘college’ means — collegial.”●

This article was published in our May 2023 issue.