In August 2021, 37 percent of U.S. K-12 teachers surveyed by the National Education Association (NEA) reported that they were considering leaving the profession.

Six months later, that number had grown to 55 percent.

Black and Latinx teachers, who are already underrepresented, were even more likely to say they were considering leaving their jobs. Among all respondents, 90 percent reported burnout as a serious issue in their careers.

The worsening shortage of teachers across the U.S. can be attributed to several factors including low pay, a decrease in classroom autonomy, and a lack of community support. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these issues and accelerated the “Great Resignation” among educators in addition to deterring students from pursuing education degrees, says Lynn M. Gangone, EdD, president and CEO of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE).

“It used to be prestigious to be a teacher,” she says. “Teachers and principals were people in the community that you looked up to. That’s not necessarily the case anymore.”

In the 10 years prior to the pandemic, the number of people who completed teacher preparation programs dropped by one-third, and total enrollment decreased by approximately 46 percent, according to Gangone. Between 2020 and 2021, 20 percent of AACTE’s member schools experienced further downslides of 11 percent or more.

“That is on top of already declining enrollment,” Gangone says. “It’s pretty sobering data.”

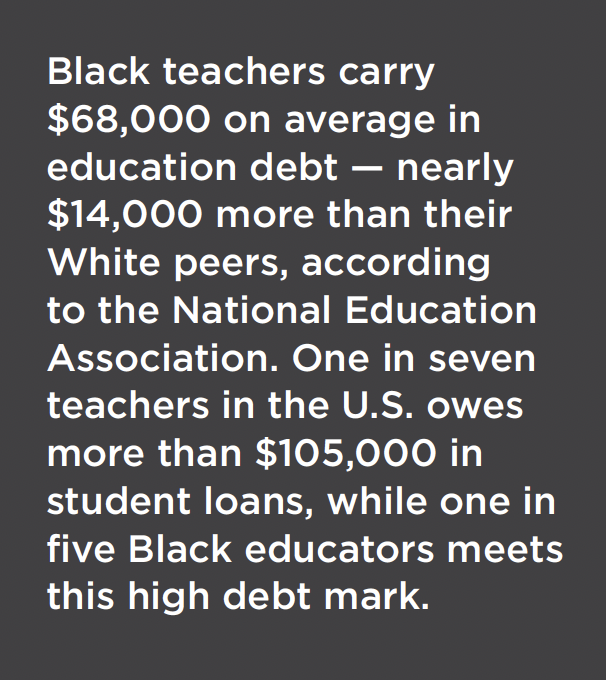

One of the most persistent barriers to attracting new teachers is low pay coupled with the high costs of education. The average starting salary for teachers nationwide was $41,163 in the 2019-2020 academic year, according to NEA data. Yet nearly half of teachers under the age of 35 owe more than $65,000 in student loans. Among those with at least 10 years of work experience, 42 percent are still paying off education debt. Educators of color are also more likely to accrue debt and in larger amounts when pursuing a teaching degree, the NEA reports.

One of the most persistent barriers to attracting new teachers is low pay coupled with the high costs of education. The average starting salary for teachers nationwide was $41,163 in the 2019-2020 academic year, according to NEA data. Yet nearly half of teachers under the age of 35 owe more than $65,000 in student loans. Among those with at least 10 years of work experience, 42 percent are still paying off education debt. Educators of color are also more likely to accrue debt and in larger amounts when pursuing a teaching degree, the NEA reports.

Institutional finances also factor into the teacher shortage, explains Gangone. Between 2008 and 2018, 40 states decreased their higher education budgets, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. This loss of state funding has meant schools of education have fewer resources to recruit, train, and financially support students. To counteract this trend, Gangone and other experts at the AACTE, the NEA, and the American Council of Education say that colleges and universities should put an increased emphasis on teacher preparation programs, build up their government relations offices to advocate for more state and federal funding, and encourage more students to pursue a teaching career.

Although finances, both institutional and personal, are key contributors to the educator shortage, the growing fight against academic freedom is causing many teachers to reconsider their career choice. As of late February, seven states had banned the teaching of critical race theory and other diversity-related concepts in public classrooms, and another 16 states were considering similar legislation. This lack of support and chilling of academic freedom has made the profession even less attractive to prospective students, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, Gangone says.

“A core question is, are we going to support our teachers and teacher candidates or are we going to make their jobs even harder?” she says. “Right now, what I’m seeing across the country, it doesn’t incentivize anyone to go into teaching.”

In contrast to these bills, some lawmakers are actually working to attract and support diverse teachers. The recently proposed EDUCATORS for America Act aims to fund teacher pipeline programs and support the development and retention of educators in classrooms across the U.S. If passed, it would provide $500 million to bolster teacher preparation programs across the country and another $500 million in grants for states to address their education workforce needs. The bill would also double TEACH grants to $8,000 per year for certain students. The grants, which were included as part of the American Families Plan in 2021, provide annual funding for educator candidates who commit to four years of teaching in high-need, low-income schools.

“Unfortunately, aspiring educators are often discouraged by high student debt, low salaries, and the lack of institutional support,” said bill co-sponsor U.S. Representative Alma Adams (D-NC) in a news release. “Educators are struggling, particularly as they continue to grapple with the pandemic. Schools are facing pervasive staffing shortages, and we can no longer afford to neglect the educator pipeline. It’s time for a comprehensive national investment in our educators.”

Government support has already proven to be key to improving the teacher shortage in some states and districts. The Grow Your Own Teacher Residency program at Austin Peay State University (APSU) in Tennessee — a state that has seen a 20 percent decrease in education majors over the last five years — is funded in part by a state grant. The program allows participants to earn an accelerated teaching degree in three years for free and to collect a salary from a local school district while completing an apprenticeship. Graduates are guaranteed employment with the district in which they trained. Since its launch in 2020, the program has expanded to seven colleges and 35 school districts throughout the state.

Another recent innovative program is Project Hispanic Educators Leading the Profession (HELP) at Texas Woman’s University, which uses federal funding to financially support Latinx women who want to become educators. Project HELP covers the cost of tuition and fees as well as state certification exams and provides academic workshops and other resources. It has been praised for addressing the workforce shortage while also diversifying teaching staff in a state where more than half of students are Latinx compared with only 26 percent of educators.

Collaboration between the government and institutions to develop unique programs such as these is crucial to resolving the teacher shortage, Gangone says. She and other education experts are worried, however, that failing to act quickly to resolve this crisis could have significant repercussions on the nation’s future.

“An educated population and citizenry is absolutely key to a democratic society,” she explains. “We need to do everything we can to make sure that there are highly qualified teachers in classrooms across the county so that kids can grow up and understand their roles as citizens of the United States.”●

Erik Cliburn is a senior staff writer for INSIGHT Into Diversity.

This article was published in our April 2022 issue.