On a sunny morning in May 2021, a crowd gathered before the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, a monument constructed last year on the University of Virginia’s (UVA) campus, to celebrate a historic moment. Governor Ralph Northam (D) was in attendance for the ceremonial signing of HB1980, which requires five state colleges and universities to grant scholarships to qualified students whose ancestors were enslaved on their campuses.

“The governor knows, as we do here at UVA, that education is the path to understanding, and that understanding leads us to reconciliation and reimagining our future,” UVA President Jim Ryan stated during the event.

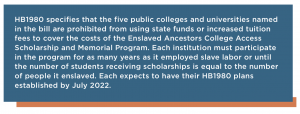

HB1980 established the Enslaved Ancestors College Access Scholarship and Memorial Program, which states that UVA, Longwood University, Virginia Commonwealth University, the Virginia Military Institute, and the College of William & Mary must identify and provide “tangible benefits” to “individuals or specific communities with a demonstrated historic connection to slavery that will empower families to be lifted out of the cycle of poverty.” In addition to scholarships, benefits may include community-based economic development programs.

HB1980’s passage is just one example of how the reparations movement is gaining traction following last year’s global push for racial justice. Shortly after the anniversary of George Floyd’s murder, the High Commissioner for Human Rights at the United Nations issued a report urging the U.S. and other countries to “confront past legacies and deliver redress” to citizens who face racial discrimination. And for the first time in more than 30 years, legislation aimed at studying and proposing methods for reparations advanced in the U.S. House Judiciary Committee.

Despite these developments, overall support for reparations remains low. In a recent poll by the University of Massachusetts Amherst, nearly two-thirds of respondents said that the government should not provide restitution to descendants of enslaved people. Younger demographics, however, tend to be more in favor of reparations, according to Tatishe Nteta, PhD, an associate professor of political science who directed the survey.

“The only groups that support [reparations] are young people aged 18 to 29, Democrats, African Americans, and Asians,” Nteta says.

Youth support for reparations is evident by the fact that students have been at the forefront of demanding that colleges and universities make concrete efforts to atone for their historical ties to slavery. In 2019, students spurred Georgetown University (GU) to become one of the first universities in the country to create a major reparations fund after they voted to institute a tuition fee to fund a scholarship program for descendants. The fee — slated at $27.20 per semester — was intended to represent 272 enslaved people who were sold by GU in 1838. Six months after the vote, the university announced that it would create a fund at its own expense instead.

In Providence, Rhode Island, Brown University pledged restitution for its historic ties to slavery by establishing a $10 million endowment to support educational initiatives in local public schools. Student activists at the university, however, say this effort is insufficient, as only 17 percent of local K-12 students are African American — meaning much of the endowment may end up benefitting students whose families were never enslaved. Furthermore, the initiative carries no provisions for identifying actual descendants of people enslaved on campus.

Unsatisfied with the university’s plan, students at Brown held their own vote in favor of reparations for descendants in March 2021.

“While the Brown family, the [u]niversity and its benefactors were enriching themselves from slavery, they were denying generations of Black Americans the opportunity to accrue wealth and achieve a better life for their families. The [u]niversity’s prosperity comes as a direct result of the oppression of Black Americans,” student leaders wrote in an op-ed for The Brown Daily Herald ahead of the vote.

The university has yet to undertake any efforts to identify descendants or meet other student demands, though it has an anti-racism task force that plans to make recommendations for redressing historic ties to slavery.

Bringing scholarship-based reparations programs into the mainstream depends on leading institutions like Brown, says Nteta. He compares the current student movement to the South African divestment movement of the late 1970s through 1980s; once students successfully pushed major schools such as Harvard University to divest, other institutions soon followed suit.

“What tends to happen in the business of higher education is that when prominent universities do something, that tends to trickle down,” Nteta explains.

This effect may already be underway when it comes to reparations, as a growing number of colleges are committing to researching the history of slavery on their campuses, says Kirt von Daacke, PhD, assistant dean and professor of history at UVA and the managing director of the Universities Studying Slavery (USS) consortium.

Established by UVA in 2014, USS began as a working group for a handful of colleges and universities exploring ties between Virginia campuses and slavery. Its membership now includes more than 70 higher education institutions across five countries. Together, they collaborate and share best practices for addressing and confronting the fact that their institutions were responsible for capturing, trading, and enslaving human beings.

Frequently, institutions become interested in joining these efforts in response to anti-racist student activism or protests on their campus. Over the course of the last five years, at least one college per month has contacted USS about joining the organization, according to von Daacke.

Many may want to offer some form of restitution for their role in this history, but the process can be complicated, he says.

“I think many schools are without a doubt interested in implementing programs that aim toward repair and redress — not necessarily a narrowly defined ‘reparations’ program — but each school has its own complex matrix of politics, structure, and alumni and student relations that shape when and how they move in that direction,” he says.

One of the most challenging aspects of carrying out such atonement is identifying descendants in the first place. Thanks to church records, bills of sale, and family histories, GU was able to trace more than 9,000 people, living and deceased, whose ancestors were once owned or sold by the university.

For other institutions, however, few if any such documents exist. Such is the case at Longwood University, which must coordinate with the state in order to fulfill its obligations under HB1980 without having the ability to identify descendants.

At UVA, researchers have spent years poring over historical documents to identify more than 900 individuals whose names are now etched onto its Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, but an estimated 3,000 names remain unknown. The university has hired a genealogist, Shelley Murphy, who created more than 100 family trees and helped organize a nonprofit organization known as the Descendants of Enslaved Communities at UVA (DEC UVA), which formally launched in 2021.

Some members discovered their ancestry after Murphy contacted them, while others knew of their connection to the school because of family oral histories, DEC UVA stated in an email to INSIGHT. The group helps locate and engage with other descendants, more of whom have come forward after UVA unveiled the memorial earlier this year. As the university continues to take steps toward restitution, DEC UVA representatives say their ultimate hope is to have their voices prioritized in the process.

“With whatever steps the university takes towards reparations,” the group stated, “our hope is that UVA leadership truly listens to people whose families have been adversely impacted by generations of slavery, segregation, and racism to make informed decisions based upon our recommendations.”●

Lisa O’Malley is the assistant editor and Mariah Bohanon is the senior editor for INSIGHT Into Diversity.

This article was published in our September 2021 issue.